N.Y. Fed: Correlation between spiraling tuition costs and rising federal aid

By Evan Lips | September 3, 2015, 13:02 EDT

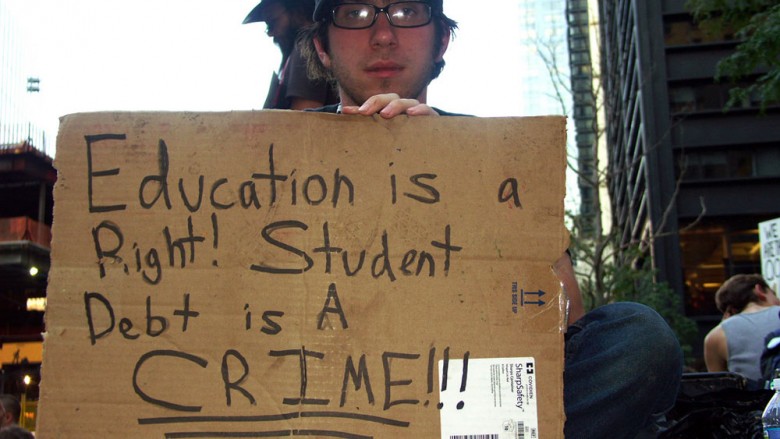

There’s a direct connection between increases to federal student aid and the skyrocketing costs of college tuition, according to a study released by the nonpartisan Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The report examined three aid programs: Federal Direct Subsidized Loans, Federal Direct Unsubsidized Loans and Pell Grants, all of which increase credit supply for students trying to pay for college.

The report’s conclusion? As the government increases spending on student aid and loans become more readily available, colleges and universities increase tuition significantly.

“We find that institutions more exposed to changes in the subsidized federal loan program increased their tuition disproportionately around these policy changes, with a sizable pass-through effect on tuition of about 65 percent,” the report said, referring to the way added credit often leads to higher tuition.

The report, titled Credit Supply and the Rise in College Tuition: Evidence From the Expansion in Federal Student Aid Programs and released in July, became the latest entry in a long-running debate over ever-increasing college prices.

Last year, the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service, or CRS, reviewed nine studies that looked at the effects of federal aid on tuition costs and said there was no consensus on whether the subsidies were responsible for increases.

“Research on the relationship between federal financial aid and college prices does not provide conclusive results in any direction,” the CRS report said.

It goes on to say that there are too many other variables (reductions in state appropriations for higher education, increased costs of faculty and staff and greater investment in technology and student services) in play to determine whether federal aid is the main culprit.

The CRS report stopped short of dismissing federal aid’s potential role in tuition increases, though.

“Even if the relationship between financial aid and price changes is not clear cut, that absence of evidence does not mean that cause and effect does not exist,” the report stated.

The debate on whether increasing aid helps or hurts students in the long run has raged for decades. The emergence of the “Bennett hypothesis” spurred the controversy that has flared periodically ever since.

In 1987, William J. Bennett, then Education secretary under President Ronald Reagan, penned an op-ed for the New York Times in which he criticized Yale University President Benno C. Schmidt Jr. for claiming that “continuing cutbacks of governmental support for student aid” was leading to tuition increases at Yale.

Back in the ’80s, Education Secretary William J. Bennett predicted that colleges would respond to increased federal student aid with tuition hikes, knowing that the expanded subsidies would blunt the impact on families.

“This assertion flies in the face of the facts,” Bennett wrote in the piece, titled “Our Greedy Colleges.”

Bennett noted that since 1982, as the federal government increased its financial support for college students, tuition rose at a far faster pace than inflation. He posited that expanded aid let schools boost prices because the higher subsidies would blunt the impact on students and their families.

Critics scoffed at Bennett’s hypothesis, and the debate has percolated ever since.

In the latest report, staff researchers at the New York Fed outlined the ties between federal aid and tuition increases, citing several statistics to demonstrate the connections:

— Between 2001 and 2012, annual student loan originations grew from $53 billion to $120 billion, with about 90 percent in recent years coming through federal aid programs.

— Federal programs have accounted for more than 90 percent of all student loans since the 2009-2010 academic year.

— For-profit, post-secondary schools (such as the University of Phoenix) derive an average of 75 percent of their revenue from tuition funded through federal aid programs;

The New York Fed staff report backs up assertions about aid-fueled tuition increases that have long been made even by professors whose salaries have grown as more and more federal education subsidies have become available.

In February 2005, then-Boston University professor Peter Wood told Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby that colleges and universities see federal education aid as money “there for the taking.”

A new report from the nonpartisan Federal Reserve Bank of New York indicates that Bennett may have been right: there’s a direct correlation between increases in federal student aid and the skyrocketing costs of college tuition.

“Tuition is set high enough to capture those funds and whatever else we think can be extracted from parents,” Wood said, according to Jacoby. “Perhaps there are college administrators who don’t see federal student aid in quite this way, but I haven’t met them.”

Wood could not be reached for comment.

Staggering growth

Significantly, increased access to student loans appears to be linked not only with increased tuition but also with the growth in administrative payrolls on many campuses.

Statistics for Bay State colleges and universities, collected by the American Institutes for Research and the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, show the following:

— From 1987 to 2011, the number of full-time administrators at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell skyrocketed 135 percent to 127 from 54. Meanwhile, the school’s enrollment rose 23 percent during that period, to 11,884 students from 9,654.

— The number of Salem State University administrators totaled 40 in 1987. By 2011, there were 113, up almost 183 percent. But enrollment climbed just 23 percent.

— Bentley University, a private school in Waltham, employed 71 administrators in 1987, a figure that grew 96 percent to 139 by 2011, while enrollment increased by only about 10 percent.

— Suffolk University, also private, led the way in boosting the ranks of administrators, with a climb of 838 percent to 272 in 2011 from 29 in 1987. At the same time, enrollment in the Boston-based school surged 165 percent to 8,850 from 3,242 — nowhere near the ballooning number of administrators.

Where will it all end?

The higher-education price bubble is beginning to deflate, suggests George Leef, director of research for the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy in Raleigh, North Carolina. On its website, the organization describes itself as a “nonprofit institute dedicated to improving higher education in North Carolina and the nation.”

“You can’t fool people forever,” Leef said in a recent interview. “The value proposition is now totally out of whack. What it costs to go greatly exceeds the benefits most people can anticipate.”

Ballooning tuition costs have far exceeded increases in medical care and housing prices, according to Mark J. Perry, an economics and finance professor at the University of Michigan-Flint School of Management. Perry used federal Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census data to compare these sectors and discovered tuition costs have climbed at about twice the inflation rate since 1978, dwarfing even the rise in health-care costs.

Reached Tuesday, Perry compared spiraling tuition costs to the housing bubble that drove up home prices during the early-to-mid 2000s.

“What led to the housing bubble was providing cheap credit to people,” Perry said. “People could pay more for housing because they were getting cheap financing.”

“If we thought the housing bubble was a problem, we need to pay attention to college tuition because the cost has gone up at a much faster rate than housing,” he said. A proliferation of subprime mortgages to borrowers who couldn’t afford to make payments in the mid-2000s is widely believed to have deepened the financial crisis that led to the longest recession since the Great Depression.

Perry said the same political desire that drove both Republican and Democratic lawmakers to create pathways, through legislation, to turn renters into homeowners is happening again when it comes to higher education.

“They have the same political obsession with college degrees,” he said. “They’ve oversold the value to both parents and students. A college student graduating with some worthless degree in anthropology would’ve been better off getting a two-year degree and becoming a plumber or an electrician.”

Yet politicians often promote increases in student aid as a way to make college more affordable, particularly for lower-income students.

Most recently, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton proposed a $350 billion plan she claims will eliminate college debt. It would steer federal cash to states that show a commitment to boosting funding for public colleges and universities over a 10-year period.

Clinton’s plan has a local booster in U.S. Rep. Katherine Clark, of Melrose, whose 5th District includes several colleges and universities, such as Bentley and Framingham State University in Framingham. Clark has said that the “costs of college are becoming further and further out of reach for the middle class and people working to get to the middle class.”

In Boston, the struggle to corral runaway college costs has put UMass and Beacon Hill leaders at odds. Senate President Stanley C. Rosenberg (D-Amherst) last week made public a letter sent to new UMass President Marty Meehan, a former Democratic congressman from Lowell, asking for reconsideration of the planned 5-percent hike in tuition and fees for the 2015-2016 academic year.

Rosenberg and Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, have said that the state’s UMass funding of $531.8 million, despite covering less than half of the system’s operating budget, should be enough to eliminate the need for a tuition increase.

In response, UMass trustees demanded more state funding.

A spokesperson for Rosenberg declined to comment.

Contact Evan Lips at [email protected] or on Twitter at @evanmlips