‘Play not the peacock’ — Washington’s Rules of Civility

By Mary McCleary | October 2, 2015, 5:58 EDT

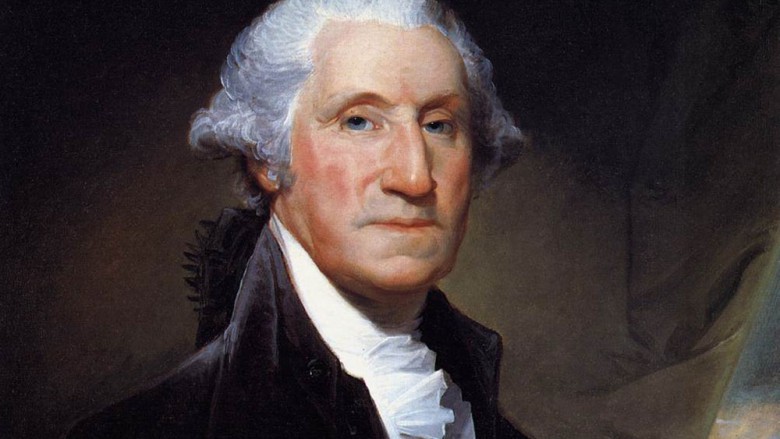

Courtesy of Wikimedia

Courtesy of Wikimedia Written when he was just a teenager, George Washington’s Rules of Civility & Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation contains 110 precepts that emphasize self-control and respect for others. It is a useful guide for young people, if only to show that basic rules of courtesy are as relevant today as they were centuries ago. While some of the quaint admonitions may cause a smirk, most of them produce a knowing nod. After all, who would dispute: “think before you speak”?

Washington wrote the instructions in a notebook sometime between the ages of 14 and 16. The original manuscript is owned by the Library of Congress. The source text was a 16th-century French Jesuit book of maxims. A tutor likely gave Washington an English translation by Francis Hawkins, which was first published in London around 1640. Historians such as Charles Moore and Richard Brookhiser believe the rules had a profound influence on the future leader, and guided his comportment throughout his life. Brookhiser also suggests that, “the rules address moral issues, but they address them indirectly. They seek to form the inner man (or boy) by shaping the outer.”

The guidelines evince his earnestness about the finer points of propriety. In time, Washington became known for his dignified presence. For instance, when a group of men was discussing his reserved demeanor at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris boasted that he could treat Washington as casually as he pleased. Overhearing the conversation, Alexander Hamilton wagered that he would treat the whole group to dinner if Morris would walk up to Washington, slap him on the back, and greet him with a hearty, “my dear general.”

At a reception afterward, Morris did just that. Washington stopped abruptly, glared at him, and slowly detached Morris’ hand from his shoulder. The mortified delegate promptly withdrew. Needless to say, no one dared repeat the gesture.

It is not that Washington was cold or uncaring: quite the contrary, his passionate leadership inspired esteem and loyalty that any commander would envy. He simply did not suffer fools gladly, especially those who provoked other people to flatter their own vanity. This sensitivity was reflected in rule 76: “While you are talking, point not with your finger at him of whom you discourse nor approach too near him to whom you talk, especially to his face.” Pointing fingers at people or standing too close in conversation are as odious today as they were in Washington’s time.

Some of the maxims are also amusing. When my children were little, I used to say, “bring your food to your mouth, not your mouth to your food,” which usually prompted a giggle. Washington’s description is even more vivid: “It is unbecoming to stoop too much to one’s meat. Keep your fingers clean & when foul, wipe them on a corner of your table napkin.” Not only did young George sit up straight, he also used a napkin instead of his trousers to wipe his “foul” fingers – another rule to remember.

Above all, Washington’s selection of maxims reflects his refinement, both in manners and personal integrity. His good breeding was based on the Golden Rule, which leads to courteous and considerate behavior. But the rules extend well beyond mere decorum. For example, “Speak not evil of the absent, for it is unjust” indicates that gossip is wrong not only because it reflects poorly on the speaker, but also because calumny destroys reputations. A similar rule is: “Be not hasty to believe flying reports to the disparagement of any.” This type of prudence was later evident in the shrewd discernment and sound judgment that defined Washington’s military and political leadership.

The Rules of Civility & Decent Behaviour is filled with many comparable gems. The finest one is the last: “Labour to keep alive in your breast that little celestial fire called conscience.”