Rose Hawthorne: Founder of the modern hospice movement

By Mary McCleary | December 5, 2015, 5:00 EST

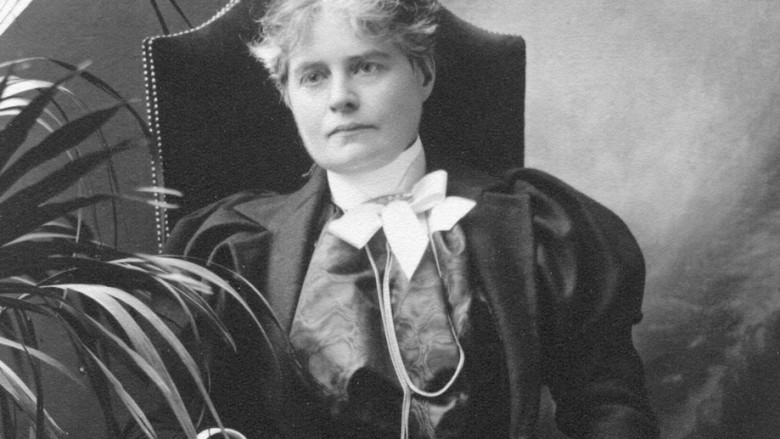

Rose Hawthorne (Courtesy of Hawthorne Dominican Sisters)

Rose Hawthorne (Courtesy of Hawthorne Dominican Sisters) Rose Hawthorne (1851-1926) was the daughter of author Nathaniel Hawthorne and his wife, Sophia Peabody. After suffering deep personal tragedy, she found solace in serving the terminally ill and the poor. Rose eventually founded the modern hospice movement, which had worldwide reverberations for compassionate end-of-life treatment.

When Rose was two years old, the Hawthornes moved to England when Nathaniel became the American Consul in Liverpool. The seven years they spent in Europe had a profound impact on the passionate, introspective Rose. During their travels through Portugal, France, and Italy, Rose’s parents taught her the importance of having faith and leading a sincere, purposeful life caring for others.

The family spent an extended period of time in Rome while Nathaniel was working on the gothic classic, The Marble Faun. The Hawthornes immersed themselves in the rich cultural surroundings of the city. After seeing Pope Pius IX during Holy Week, Rose wrote: “I became eloquent about the Pope, and was rewarded by a gift from my mother of a little medallion of him and a gold scudo with an excellent likeness thereon, both always tenderly reverenced by me.”

The Hawthornes returned to Concord, Massachusetts in 1860. Four years later, sadness descended on the family when Nathaniel died while traveling in New Hampshire. Unable to sustain the high costs of her children’s education, Sophia decided to relocate to Dresden, Germany.

During their stay in Dresden, Sophia met an American student, George Parsons Lathrop. After the Hawthornes moved to England during the Franco-Prussian War, tragedy struck yet again when Sophia died in 1871. Feeling anxious and alone, Rose decided to marry George Lathrop a few months later. Her relatives were against the marriage, citing George’s unstable character and Rose’s inability to make a serious commitment while deeply grieving her mother.

The marriage was strained from the start due to George’s alcoholic irascibility and their financial difficulties. The couple decided to return to the States, and became active in social and literary circles. George worked as a novelist and associate editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and Rose published poetry and short stories.

Sorrow overshadowed their lives when their only child, Francis, died of diphtheria at 5 years old. Seeking consolation in her faith, Rose and her husband eventually converted to Catholicism in 1891. With time, however, George’s alcoholism and abusive behavior became so dangerous that Rose obtained a permanent separation in 1895, with the approval of the Catholic Church. Three years later, George died from cirrhosis of the liver.

Devastated by the loss of her child and marriage, Rose sought a meaningful direction for her life. That moment came during a life-changing conversation with a priest about the death of a poor seamstress. Alone and dying of cancer, the desolate woman was unable to afford treatment. She was sent to the city’s notorious Blackwell’s Island, home of prisons and sanitariums, where she died without medical care. As she listened to the story, Rose recalled “A fire was then lighted in my heart, where it still burns … I set my whole being to endeavor to bring consolation to the cancerous poor.”

With her newfound purpose and determination, the 45-year-old Rose completed a nursing course and opened a home for poor incurable patients in New York City’s Lower East Side. In addition to cancer patients, Rose helped other underprivileged people. She paid rent for young widowed mothers, did housework and cooked for the children of her cancer patients, and assisted elderly neighbors with their ailments. Rose published a memoir of her father to support her activities.

As the enterprise grew, other women joined her to care for the sick. Rose eventually founded a religious order (later known as the Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne), operating seven hospice facilities in six states. Adopting the religious name Mother Mary Alphonsa, Rose emphasized the sanctity of life, exhorting her helpers to remember that each sufferer has “the image of God in their souls.” She welcomed every poor person regardless of religion, race, or nationality, saying that “One soul is as fair and precious as another — there is no exception.”

Today, the Hawthorne Dominican sisters continue their foundress’ legacy of providing loving care for the terminally ill. Their homes are free for needy patients, and are a treasured part of their local communities.

I recently contacted the Superior General of the order, Sister Mary Francis Lepore, for her insights.

Please describe how Rose Hawthorne (Mother Alphonsa) saw the inherent dignity of life in her patients, especially the terminally ill.

There is a well known event in “Glimpses of English Poverty” by Nathaniel Hawthorne that speaks of a young child who was very sick and disheveled. The gentleman in the story picks him up and hugs him, understanding the inner beauty of each person: “It was as if God had promised the child this favor on my behalf, and that I must needs fulfill the contract.” From an early age, Mother was imbued with the value and dignity of each person. Through her own suffering she received strength from the knowledge of God’s love for her and His Providence. She sought through prayer to serve God by helping others, especially the very poor and to alleviate the suffering of those most in need. She actually wished to serve the poorest of the poor. She determined that those poor suffering with incurable cancer were the most destitute. Cancer was thought to be contagious and the poor were often forced out of their home and sent to die in Blackwell’s Island away from their family.

How do the current sisters help patients face their serious illnesses?

Our care is not merely physical care. We attempt to give each of our guests the support they need both physically and spiritually. We, like Mother, care for them and love them as members of our family. The same Sister will care for particular patients until they die. In this way, our guests know they are important and they are loved. That is the most important thing we can give to them — our love and our concern for them. It is a home of joy and peace. … Life is a precious gift and it is lived fully at our Homes. Those who enter our home continue to be referred to as our guests as Mother always wanted to have them feel it was their home. And they in turn teach us many valuable lessons of life, especially surrender and trust.

Rose Hawthorne suffered personal tragedy in her life with the deaths of her beloved parents and only child, and her shattered marriage. Yet instead of bitterness, she transformed her sorrow into sympathy for terminally ill outcasts. As the founder of the first hospice care system, Rose’s vision of merciful end-of-life treatment revolutionized the lives of millions of patients around the world.

The Catholic Church opened the cause for Rose Hawthorne’s canonization in 2003. On March 4, 2014, the Vatican approved the initial diocesan phase, and her process was advanced to the next stage.

Contact Mary McCleary at [email protected].