Nonprofit Colleges Pay Small Fraction of City Taxes

By Stephen Beale | February 2, 2017, 6:14 EST

Harvard University, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Museum of Fine Arts, and other nonprofit colleges, hospitals, and cultural institutions are indispensable to Boston’s identity as a world-class city. But, when it comes to city finances, there’s a huge downside.

The proliferation of tax-exempt institutions in Boston — at least nearly 50 in all — leaves a smaller share of taxpayers, such as homeowners and businesses, to pay the tax burden — all the while nonprofits continue to benefit from city services.

Nonprofits are protected under state law from having to pay local property taxes.

Otherwise, the city would be raking in nearly half a billion in taxes on the $13.7 billion in land and buildings the nonprofits own.

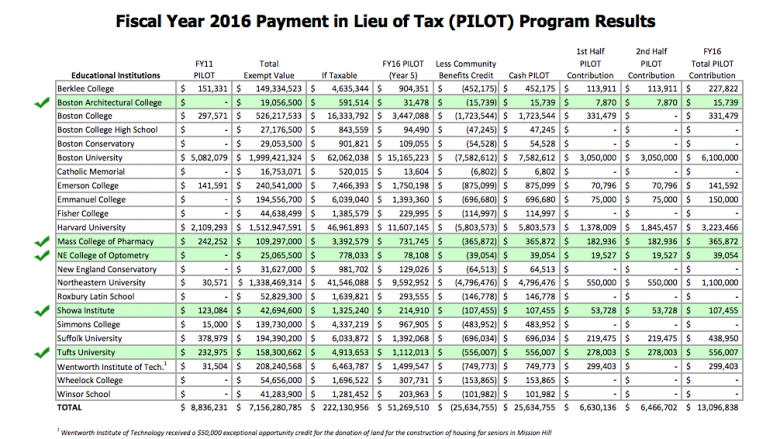

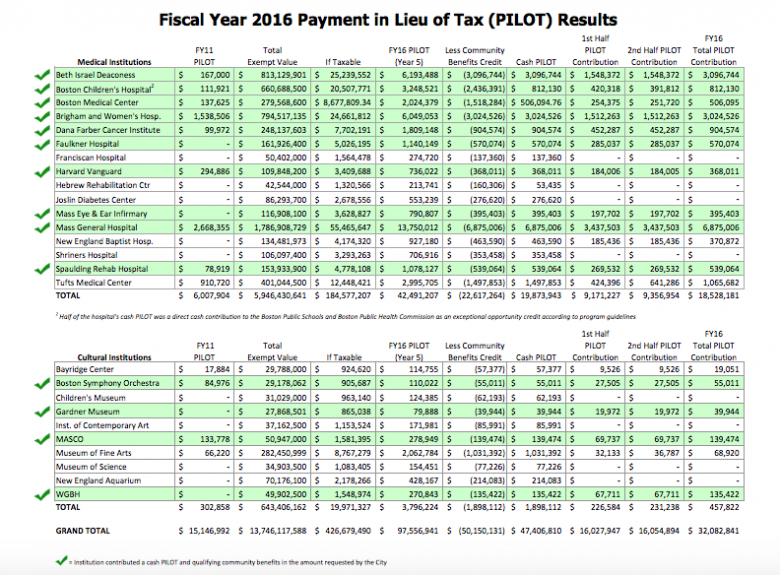

Amid calls for these nonprofits to pay their share of the cost of city services, a number have stepped up, making voluntary payments in lieu of taxes (known as PILOTs). In 2016, those payments amounted to $97.5 million, about 22 percent of what they’d otherwise owe.

The problem: just five of the 23 nonprofit schools give the city what it asks for. They were: the Boston Architectural College, the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy, the New England College of Optometry, the Showa Institute, and Tufts University. (Nonprofit hospitals and cultural institutions comply at a far higher rate.)

Topping the list is Boston University, which has $1.9 billion worth of buildings and land in Boston. If it weren’t tax exempt, those properties would yield $62 million in taxes. Instead, BU pays Boston about a little less than an eighth of that — $7.5 million. (Total contributions are estimated at $15 million, but an estimated amount of “community benefits” for each college is deducted. In the case of BU, its benefit to the community is estimated at $7.5 million.)

When asked why it wasn’t giving the city what it says it needs, a university spokesman stressed the voluntary nature of the program and noted that, among the listed schools, BU is the top contributor. Colin Riley, the spokesman, did not elaborate on the methodology or reasons BU submitted a lower amount, other than to say it contributed an amount it deemed “appropriate.”

He also noted that BU maintains two financial aid programs directly tailored to Boston students. One is the Thomas M. Menino Scholarship which covers all tuition costs for four years and is awarded to 25 seniors from public high schools in Boston. Riley said the program was expanded in December to include transfer students. A second program, the BU Community Service Award, helps local students attend the school without having to take out any loans.

After Boston University, Harvard ranks second highest for property value and payments to the city. Although Harvard is based in Cambridge, it has $1.5 billion worth of properties in Boston. For example, Harvard Medical School is situated in Boston, as is Harvard Business School.

Harvard, which has a $36.4 billion endowment — the largest of any U.S. educational institution — pays the city $11.6 million in tax payments, though that amount is cut in half to $5.8 million once Harvard’s community benefits are factored in. Without its tax-exempt protection, Harvard would have to fork over $46.9 million in taxes to Boston.

The university did not respond to formal request for comment.

In at least one case, the community benefits recorded by the city understate the difference an institution really makes in the city. Although the city says Boston College provides an estimated $1.7 million in community benefits, a spokesman suggested that the real amount is much higher.

“As a Jesuit, Catholic university that is committed to service, we believe that the best way we can assist the City of Boston is through the more than $30 million in community benefits that we provide to the city and its residents each year through scholarships, jobs, volunteer outreach, community grants and the public and private grants we procure for Boston’s public and parochial schools,” said the spokesman, Jack Dunn.

In the first half of 2016, BC paid Boston $331,478, an amount that Dunn said had been agreed upon through a municipal service agreement apart from the PILOT program, which he noted is voluntary.

Despite the discrepancy between what the city requests and how much colleges and universities actually pony up, the city administration remains upbeat about the PILOT program. A spokeswoman for Mayor Marty Walsh noted that payments under the program have increased by $16.9 million, or 111.8 percent since 2010 fiscal year.

“We are encouraged by the continued increase in PILOT payments, and in particular by the contributions of the medical sector. We will continue to work with all institutions to maintain and increase this program’s success,” Walsh said in a statement provided to New Boston Post.

In 2012, Boston ranked fifth among the top 20 most populous states in terms of the percentage of property that is tax-exempt, according to a survey by Governing magazine. That year $34.8 billion — or 29.3 percent of all properties—was exempted from having to pay taxes. (New York City topped the list with 42.2 percent of its properties exempted while Indianapolis was last at 7.5 percent.)

Municipal finance experts warn that exempting large numbers of properties increases the tax burden on homeowners and businesses. The pressure becomes particularly acute as city costs rise while nonprofit colleges and universities expand their footprint in a community.

A 2008 report from Community Labor United, an advocacy organization for low- and middle-income neighborhoods and unions, warned that tax breaks for nonprofits — particularly academic medical centers — was shifting too much of the burden onto taxpayers, especially homeowners. “The loss of tax revenue from valuable, otherwise taxable land in cities with few remaining undeveloped parcels puts a double squeeze on taxpayers and on consumers of public services,” the report stated.

In the years immediately since the publication of that report, tax rates continued to rise in Boston. For commercial payers, the rate went from $27.11 to $31.18 per $1,000 in value, between 2009 and 2014. In 2015, the rate eased down somewhat but was still ranked 37th highest in the state according to the Boston Business Journal.

The residential rate, while notably lower, has also been on the upswing. During the same period it went from $10.63 to $12.58.

Recent budgets have given taxpayers a little more of a break — although rates are not yet back to what they were before 2009. In 2016, the residential rate eased down to $11.00 and the commercial rate was $26.81. (A major factor in the decrease is reportedly a boost in the assessed values of properties, which means that residents were not necessarily paying less in taxes.)

Aside from relief to taxpayers, the city also faces massive infrastructure costs.

In a Boston Globe column earlier this month, Walsh announced a program to revitalize the infrastructure for city schools, about half of which, he said, predated World War II.

The estimated price tag? $1 billion over 10 years — equivalent to how much the city would receive if nonprofits collectively paid double what they contribute today, which would still be half of what they otherwise would owe if they were regular taxpayers.