New England’s Pro Sports Franchises To ‘Take the Lead’ Against Racism

By Evan Lips | September 28, 2017, 17:38 EDT

BOSTON — Days after hundreds of National Football League players who took a knee or linked arms during the national anthem helped inject a healthy dose of politics into sports, representatives from New England’s five major league sports franchises gathered at Fenway Park to launch a new anti-racism initiative.

Dubbed “Take the Lead,” the initiative features a public service announcement — played for the first time on Fenway Park’s video scoreboard Thursday — which state Senator Linda Dorcena Forry (D-Dorchester) noted sends a “unified message to every fan attending games throughout this season.”

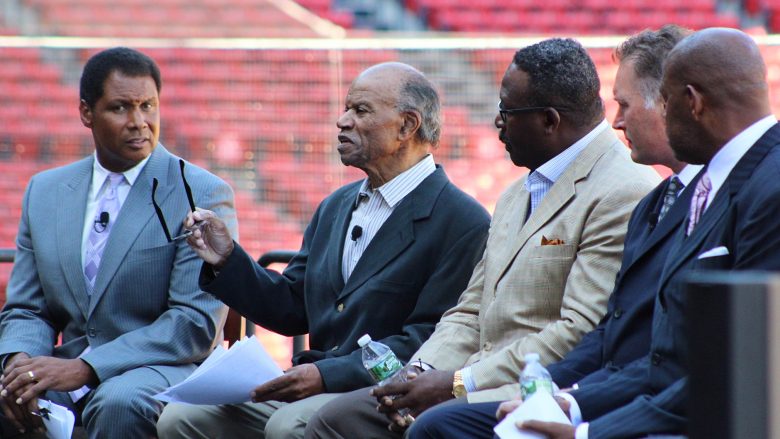

The day also saw a star-studded panel of former Hub athletes gather at makeshift podium created atop the Boston Red Sox dugout to converse about racism, months after several alleged high-profile incidents involving fans roiled the organization.

Cedric Maxwell, a former standout for the Boston Celtics who now does radio duty for the team, was the lone player to call out President Donald Trump. Trump last Friday made headlines when he suggested that NFL team owners should fire players who elect to take a knee during the singing of the Star-Spangled Banner.

“You learn that it’s not just about sports, you learn that sports can be a barrier that can overcome racism, and that’s why I’m so — and I’ll just put it out there — I’m so appalled at what our president has done,” Maxwell told panel moderator Steve Burton of WBZ-TV.

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh spoke ahead of the panel and said the kneeling trend and the “power of sports is bringing a conversation to the United States of America right now, in our football

The Boston Red Sox “Take the Lead” banner hangs above the left field scoreboard at Fenway Park. (Evan Lips — New Boston Post)

stadiums and in our basketball stadiums and other stadiums.”

He also took a veiled shot at Trump.

“The national conversation has been ugly at times, some voices in Washington aren’t helping us, but there’s no reason why we should shy away from the conversation of race,” he said. “Our role here in Boston should be to take the lead.”

Walsh, who is now in the midst of fending off a mayoral challenge from former Roxbury City Councilor Tito Jackson, who is black, also pointed to the city’s recent commissioning of a statue honoring Martin Luther King Jr..

“The decision to build the memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King is one of a lesson in progress that just didn’t happen by itself,” he said. “We’re not just building a statue, we’re beginning a conversation and dialogue about the words that he said and what he meant.

“His words are more true today than they arguably were when he spoke them in the 1950s and 1960s.”

Maxwell, however, also shared a story of a different sort. The former 1981 NBA Finals MVP talked about how he first treated Celtics rookie Larry Bird when the Indiana native joined the team.

“You have to realize that racism is alive and well and it happens on both sides,” Maxwell said. “People of color, I can say that an example of that was me and my first day meeting Larry Bird — I had already been in the NBA for two years, so I’m watching him come in and I’m clapping like this, going, ‘great white hope, here he comes.’

“Well after about an hour or two of him knocking down all these jump shots, I’m thinking, ‘damn that white guy can play’.”

Maxwell recalled that Celtics players were “despised” outside of Boston, especially in black communities, but noted that he saw things begin to change when he walked into a black barbershop and saw Bird’s photo on the wall.

Fellow panelist Tommy Harper, who played for the Red Sox and later served as a coach in the organization, shared his story about the time he spoke out when during spring training he noticed that representatives of the local Winter Haven Elks Club would enter the team clubhouse to hand out membership invitations to white players.

“This went on from 1972 until 1985 until a writer from the Boston Globe approached me,” Harper recalled. “I told him the truth. I didn’t make up anything. Eventually I was fired because I spoke up against the practice.”

Burton later asked Harper at what point he believes the Red Sox finally got out from under the cloud of racism that followed the team. Harper pointed to current Red Sox owner John Henry’s purchase of the franchise in 2002. Harper talked about the response the franchise took following two notable incidents that occurred earlier this season, including one in which Baltimore Orioles outfield Adam Jones claimed a fan lobbed racial epithets at him.

“Historically African-American baseball fans and players fearful of being harassed have stayed away from Fenway Park,” Harper said. “Certain behavior that would make people feel unwelcome is no longer tolerated — the response to the Adam Jones thing is what I take away.”

The Jones incident has been disputed, however, as the only fan who publicly claimed to have heard the slur saw his story begin to crumble under scrutiny. Walsh, however, subtly referred to the challenge of fans deciding whether to speak up after witnessing such incidents.

A more well-documented incident occurred later that same week after the black father of a biracial child told the Boston Globe that another fan whispered a slur to him in response to the singing of the national anthem by a Kenyan woman. The fan was never publicly identified. Red Sox officials say the action earned him a lifetime ban from Fenway Park.

“If a Yankees fan gets up in Fenway Park and talks trash, he’s going to hear about it from his whole section,” Walsh said during his remarks. “If a person says something racist, in any public or private space, that reaction should be one hundred times stronger.”

Burton also asked Harper whether he thinks the city should rename Yawkey Way, named in honor of deceased Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who has drawn criticism over his unwillingness to sign black baseball players.

“As far as the Yawkey sign, I think it’s up to the abutters of the street and it’s up to the Red Sox to figure this out,” he said. “I don’t really call anyone a racist or use those kinds of labels, all I do is look at the policies, I look at what’s happened over the last years.”

Red Sox President and CEO Sam Kennedy said he’s “not here to call anyone a racist, especially someone I’ve never met,” referring to Yawkey, who died in 1976.

“Yawkey Way is a symbol that has really been an issue we’ve been focused on,” he said. “We made the decision — John Henry made the decision — he sent a loud and powerful message that he’d like the Red Sox to petition the city to change the name of Yawkey Way because it’s a powerful symbol of a time when this ballpark and the era might not have been as inclusive and as welcoming as it should have been.”

Former Boston Bruins player Bob Sweeney was also a panelist and pointed to his experience in the early 1980s when he was an American trying to break into a league that was dominated by Canadians. Sweeney, who grew up in Massachusetts, used college as his springboard into the National Hockey League.

“We were labeled as the college kids that weren’t tough enough,” he said. “I think we proved them wrong and now it’s great to see so many college kids and Americans in the NHL.”

Sweeney also touched on issues of race when he recalled his time playing in Buffalo alongside black goaltender Grant Fuhr, and the Bruins’ decision to draft black netminder Malcolm Subban in the first round of the 2012 NHL draft.

“I looked at Grant as one of the best of all time and not African-American,” Sweeney said.

As for Subban, Sweeney, now the executive director of the Boston Bruins Foundation, said “it didn’t matter if he was African-American, at that time, we thought he was the best prospect, and that’s why we took Malcolm Subban.”

Both Subban and Fuhr were born and raised in Canada.

(Evan Lips — New Boston Post)

Former New England Patriots linebacker Andre Tippett, who wound up in Foxborough after being drafted by the team in 1982 after playing collegiately at the University of Iowa, said he was hesitant about living in the region. He recalled friends telling him to avoid South Boston. Tippett, who now lives in Sharon with his family, said things have changed drastically since those days.

Tippett praised the diversity of Sharon.

“You hear all those things and I live in a great community now, in Sharon, we’re such a diverse community there that my kids are free to do whatever they want,” Tippett said. “I’ve always made my children aware of a lot of things. They’re biracial. Be aware but don’t judge anybody until you see how they react. I’ve been here for 35 years. I’ve had a fabulous second career here.”

According to the latest data available from the United States Census Bureau, the town of Sharon, located northeast of Foxboro, boasts a population of a little less than 18,000. Demographic data shows that the town is 79 percent white, a little less than 5 percent black and about 14 percent Asian.

Asked to reflect on the trend of NFL players kneeling during the anthem, Tippett, who now serves as the team’s director of community affairs, said the decision to take a knee last Sunday “looked a little out of character” for the rigid franchise.

“But when I thought about what was going on it brought me back to the fact we live in a democratic society — as long as you’re not hurting anyone you’re free to do what you want,” he said. “The fact we locked arms and took a knee as a team, as cliche as it sounds, we were doing it as a patriotic community and I was proud.”

Thursday’s program also saw remarks from Tanisha Sullivan, the president of the NAACP’s Boston branch, and Roxbury Presbyterian Church Reverend Liz Walker. Walker said the plan to launch “Take the Lead” began several months ago but stressed that “the recent events gave this gathering a far greater urgency.”

Governor Charlie Baker was not in attendance but did tape a message that played on the park’s video scoreboard.

“Massachusetts is proud to be the home of an inclusive, multicultural, welcoming, and global community,” Baker said. “The commonwealth, Boston, and our communities and schools stand for open-mindedness, unity and tolerance.

“Unfortunately in recent months disturbing and intolerable demonstrations of racist behavior have challenged our communities, our state and our nation — but the actions of a few are not who we are as a commonwealth.”

The fifth major sports team involved in the initiative, the New England Revolution of the Major League Soccer, did not feature a player on the panel, but did send Brian Bilello, the team’s president, as a representative.

Thursday’s event occurred hours before the kickoff of a game between the NFL’s Green Bay Packers and Chicago Bears.

The Packers, who are hosting the evening tilt, have asked fans to show solidarity with the players by kneeling, sitting or locking arms during the singing of the national anthem.