Gina Raimondo: Rhode Island’s Little Engine That Can

By James P. Freeman | January 30, 2018, 21:14 EST

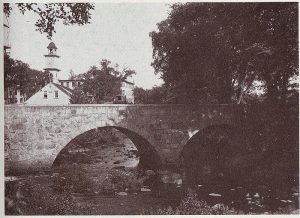

For over two hundred years water has flowed underneath a bridge in the Blackstone Valley corridor of the smallest state in the union that, over one hundred years ago, powered the largest and most modern textile mill of its day, which helped launch the Industrial Revolution. The Slatersville Stone Arch Bridge, the oldest masonry bridge in Rhode Island, was built in 1855 to replace the original wooden structure; it’s now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. For decades neglected and structurally deficient beginning this young century, it’s undergoing a complete rehabilitation for $13.5 million. The bridge is symbolic of the state’s roaring-rapid rise and fall. And now its revival.

Much of that effort is being spearheaded by Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo.

Amidst the partisan tempest — The Great Political Uncentering — Raimondo, 46, the state’s first female executive, stands in defiance of recent history. And political trends. Seeking reelection in 2018, her public service has been a series of calculated experiments: She is arguably the nation’s most consequential reform-minded, results-oriented politician. She is resuscitating an extinct species (Truman Democrats). And she is a pro-growth moderate. Heavy turbulence included.

For the most insular and parochial state — where Coffee milk is the official state drink, Catholic Mass is still televised on Sunday mornings and, remarkably, New England Cable News is not offered for viewing by the largest telecommunications provider — the last decade was particularly cruel. Nothing went as planned and many plans went for nothing.

In the wake of The Great Recession of 2008-2009, Rhode Island’s already corroded economy saw unemployment spike close to 12 percent while housing prices plunged by 27 percent. In 2010, after luring it away from Massachusetts, the state financed Curt Schilling’s scandal-plagued video-game start-up, 38 Studios, with $75 million in bonds before the company went bankrupt two years later. And in 2011, sparking national headlines, Central Falls, a city with a population of 19,376, covering an area a little over a square mile (more densely populated than Boston), filed for bankruptcy, raising concerns that other municipalities in the state (including its capital, Providence) might follow suit.

Residents probably needed a professional psychologist to lead it out of its depressed state but instead chose a thoughtful capitalist; Raimondo — a Rhode Island native with degrees in economics (Harvard), sociology (Oxford), and law (Yale), and cofounder the state’s first venture capital firm, Point Judith Capital — was elected State Treasurer in 2010. So began the secular resurrection.

Raimondo understood a law of modern politics that many public officials refuse to acknowledge or act upon: demographics is destiny. Rhode Island’s aging population coupled with a hemorrhaging fiscal condition exacerbated by the recession, and overly generous and ambitious yet underfunded pension plans, were certain to wreak financial havoc not just on local municipalities but could also render the state itself insolvent, leading to collapse. That would be unchartered territory. (A state declaring bankruptcy is not a contingency properly addressed under current bankruptcy laws; imagine that resolution.) The treasurer did something remarkable. She conducted town hall-style meetings underscoring the severity of the problems. And she told the unions and pensioners something no Democrat ever says to those loyal constituents: “No!”

She suspended cost-of-living increases and raised the retirement age for retirees and engineered an overhaul, pointing the system towards solvency. Raimondo also understood state law. While many state pension systems are determined by contract (making modifications more difficult under constitutional law), Rhode Island’s was by statute, allowing the government, if so inclined, to make changes via the legislature, not protracted judicial settlements.

Changes were implemented. The crisis averted.

Predictably, though, public-sector unions fulminated and sued. A September 2014 Washington Post editorial concluded, “In the face of ferocious opposition from labor, she explained the plain budgetary impossibility of maintaining pensions at the levels promised by politicians in Providence.” Still, she was able to win the governorship that year with 41 percent of the vote in a three-way race. In 2015, she negotiated legal settlements that preserved the reforms in the face of continued legal opposition. Her efforts are proof that pension reforms can be administered and may prove to be a model for other states suffocating under such massive obligations.

Just after Raimondo was elected governor (the first Democrat in over 20 years to win the office in heavily Democratic Rhode Island) and after the national Republican landslide in 2014, The Daily Beast’s Joel Kotkin demanded Democrats return back-to-the-future: Time to Bring Back the Truman Democrats.

“To regain their relevancy,” he hypothesized, “Democrats need to go back to their evolutionary roots. Their clear priorities: faster economic growth and promoting upward mobility for the middle and working classes. All other issues — racial, feminine, even environmental — need to fit around this central objective.” Raimondo, perhaps instinctively, embraced many of these themes. Much of it via a back-to-basics moderate agenda, too.

In February 2016, she launched Rhode Works, a comprehensive ten-year transportation improvement program to repair crumbling roads and bridges. Rhode Island ranked dead last (50 out of 50 states) in overall bridge condition and was one of the only states that did not charge user fees to large commercial trucks on its roadways. Tolling on certain road begins this winter. And, again, she is facing union opposition; this time from trucking associations. Leery of the legislation, citing discriminatory practices, the associations are threatening lengthy lawsuits. This infrastructure initiative might be a template for the anticipated trillion-dollar federal program.

Raimondo has looked north for much of her inspiration, home to another successful moderate.

In her fourth State of the State address this month she made this startling admission: “For decades, we just sat back and watched as Massachusetts rebuilt and thrived. Boston and its suburbs flourished, while the mill buildings along 95 and the Blackstone River stood vacant and crumbling. The resurgence in Massachusetts didn’t just happen. It wasn’t an accident. They had a strategy and a plan to create jobs and put cranes in the sky. They used job training investments and incentives to create thousands of jobs in and around Boston.”

Why not study a success story?

Unlike many parochial powerbrokers of the past who were content on resisting change, at the state’s peril, Raimondo recognizes that Rhode Island’s is a regional economy. In many ways it depends on Massachusetts’s economy. Two-thirds of Rhode Island’s population is within a twenty-minute drive to any Massachusetts border. Indeed, she made the trip at least twice last year by appearing on WGBH’s Greater Boston program, marketing her ideas and progress.

Massachusetts’s Charlie Baker is the most popular governor in the country with a 69 percent approval rating. He, too, is a moderate (think Rockefeller Republican), a technocrat, and up for re-election in 2018. While Raimondo’s most recent approval rating stands at only 41 percent, that figure may be distorted and artificially low. Baker’s reforms have centered on the inner workings of government, largely lost on everyday residents. Raimondo’s reforms, meanwhile, have been about the very outward and public machinations and expressions of government. Her actions have directly affected the entire electorate.

Today, Rhode Island’s unemployment rate is 4.3 percent. Last March, The New York Times wrote, “Ms. Raimondo’s frenzy of economic and job development is striking because Rhode Island has long been in a slump. It was the last state to emerge from the recession that began in 2007. As recently as 2014, it bore the nation’s highest unemployment rate for seven months in a row.” At the same time, private-sector employment has reached its highest level ever.

Even with forward momentum, the governor may be more popular outside the state. Two years ago, Raimondo and then-Governor Nikki Haley of South Carolina were cited by Fortune Magazine as two female governors being among the world’s 50 greatest leaders. And last month, she was named as new vice chairman of the Democratic Governors Association.

Big challenges still loom large locally. The Pawtucket Red Sox, Boston’s AAA affiliate, are threatening to leave the state. (Will the public finance a nine-figure stadium for a rich, privately-owned team?) Nearly a third of the state budget ($3.1 billion) is funded by the federal government. And opioids continue to consume lives.

But due to Raimondo’s centrist leadership — despite the occasional progressive flourish (like tuition-free community college) — she has largely validated Kotkin’s hypothesis by focusing primarily on economic matters. Rhode Island might finally be poised for a 21st Century renaissance.

As the Slatersville bridge undergoes its third iteration in its third century, Rhode Island voters are reminded of this possibility in 2018, the Year of the Woman. Should Raimondo be re-elected and serve a full second four-year term she would be just the third woman (all Democrats) in American history to do so (after Michigan’s Jennifer Granholm and Washington’s Christine Gregoire).

Then again, with the Clintons finally out of power, serious Democrats must consider her record of accomplishment vice presidential timber in 2020.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer and former columnist with The Cape Cod Times. His work has also appeared in The Providence Journal, newenglanddiary.com and nationalreview.com.

Stone Arch Bridge in Slatersville, a village of North Smithfield, Rhode Island, was built in 1857.