How faith’s like learning a language

I don't know if you could say that we've carved out a "normal" for ourselves yet,six weeks into living in Crete, but things are definitely feeling a little more stable. The chore chart's back in action for the first time since June. We have our weekday activity schedule – gymnastics Tuesdays and Thursdays, tennis Wednesdays and Fridays. And we've started doing stuff recreationally on weekends – "participating" (quotes necessary) in an evening Chania 5K race with two other families; attending an American Halloween party; taking bike rides through the trails behind our house… plus in the driveway all the time. Turns out a steep, paved driveway's a total perk. I visited a Cretan ear doctor last week and really liked her – found her well-informed, knowledgable, attentive. A reassuring first step since I need to either get a tube inserted in my crazy misbehaving ear, or go to Athens to get my hearing aid adjusted (my manufacturer has no service providers on Crete), or both. I see her again this week.

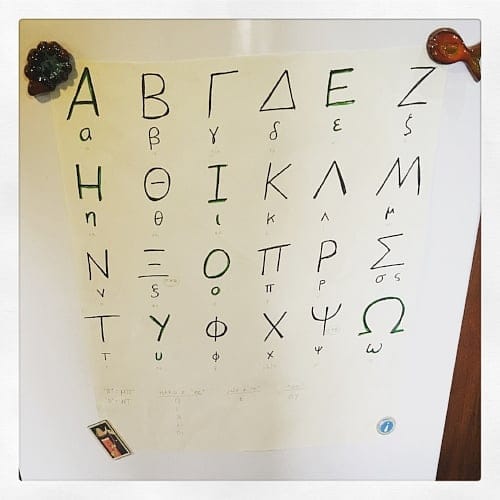

Something that occupies a lot of our time now – my husband's and mine – is Greek. It's kind of addicting. He has the Pimsleur program and we listen to a lesson occasionally in the evenings. But more often, we just amass new words each day – through Greeks we encounter or just Google translate – and work on learning and using them. It's basically 'Greek-lish' all the time at our house. At first the kids were reluctant to get involved: words seemed hard to remember, and they just didn't care that much.. Two things happened to kickstart their involvement. The first was a purported school Greek test (I'm not sure it even happened) which prompted us to create a massive Greek alphabet, tack it to our fridge, and go through it repeatedly with them. Once this was done, the oldest kids became intrigued with the idea of writing English names using Greek letters – their own, Captain America, Star Wars, etc. It's like knowing how to use a secret code – pretty cool. The second was my husband's ingenuous idea to reward their efforts to learn and incorporate Greek phrases by handing out Pokemon cards. Pokemon fever has fully and officially swept our household- all four kids – and this turns out to be remarkable incentive for all of them.