The Quasi-War decision that saved the nation

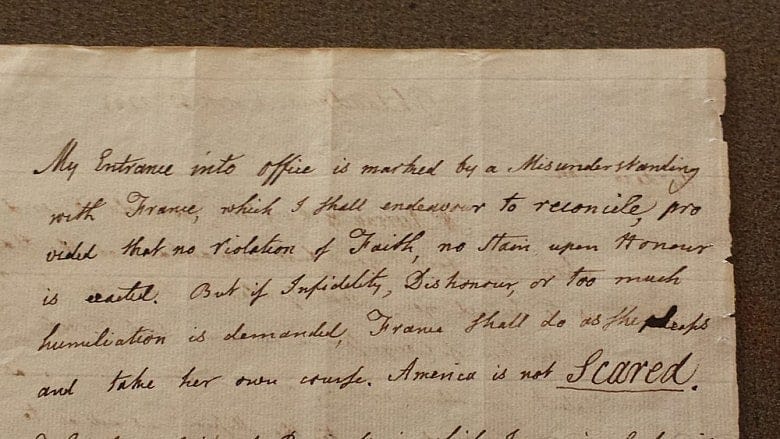

Like David to Goliath, President John Adams responded to French naval aggression by boldly stating, "America is not scared." During the Quasi-War with France, Adams fortified the nation's scant defenses and ordered a muscular retaliation against French hostilities. But Adams also persisted in sending envoys to negotiate peace, which historian David McCullough called the bravest act of his career. With the remarkable foresight of his carrot-and-stick approach, Adams averted a full-scale war that his fledgling country was almost sure to lose. By procuring peace with Napoleon, Adams also paved the way for the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the country's size and secured America's future against hostile international powers.

In 1794, the French Revolutionary government objected to America's Jay Treaty alliance with Great Britain. Tensions further escalated over loan financing disputes. After Congress ratified the Jay Treaty in 1795, France began seizing American ships. When Adams became President in 1797, simmering hostilities were boiling into war.