Discovering manuscripts: New dilemmas meet old solutions

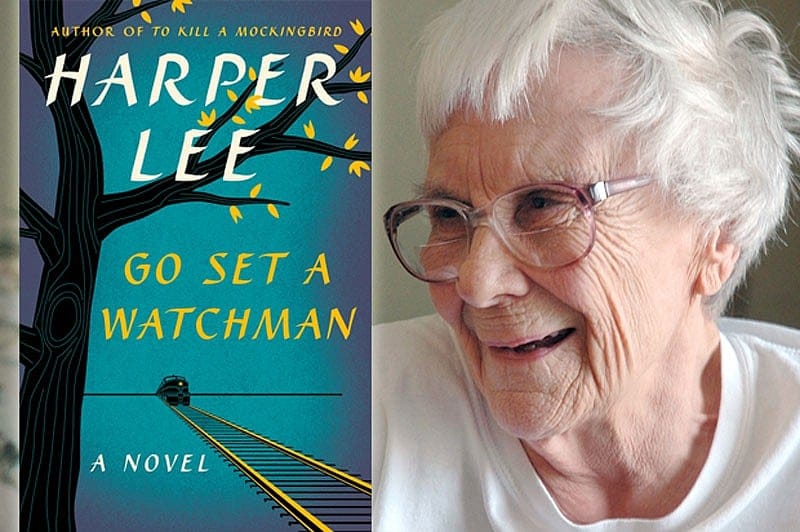

The recent discovery of 10 lost plays by the beloved mystery writer Agatha Christie highlights a lucrative trend in the publishing world. In this year alone, a host of "newly discovered" writings by J.R.R. Tolkien, Harper Lee, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Dr. Seuss have enjoyed considerable commercial success. With each case, the same questions arise: how do we discern, and to what extent do we honor the wishes of the author when reproducing the work? Does the public have a right to see these works? Should publishers exercise creative editing to complete unfinished manuscripts?

As ravenous consumers of our favorite authors, it is easy to be blind to the finer ethical points. Yet would any of us feel comfortable having the creative output of our college days published for the entire world to see and inevitably compared to our more mature work, as in the recent case of Tolkien's The Story of Kullervo? The publication of Go Set A Watchman is a case in point: Initial hype soon gave way to disappointment.