Andover nonprofit’s free medical gear helps women, babies survive

NORTH ANDOVER – As it sought to supply less-developed countries with refurbished American hospital gear, International Medical Equipment Collaborative determined that it was delivering something more significant, by enhancing the well-being of women and children.

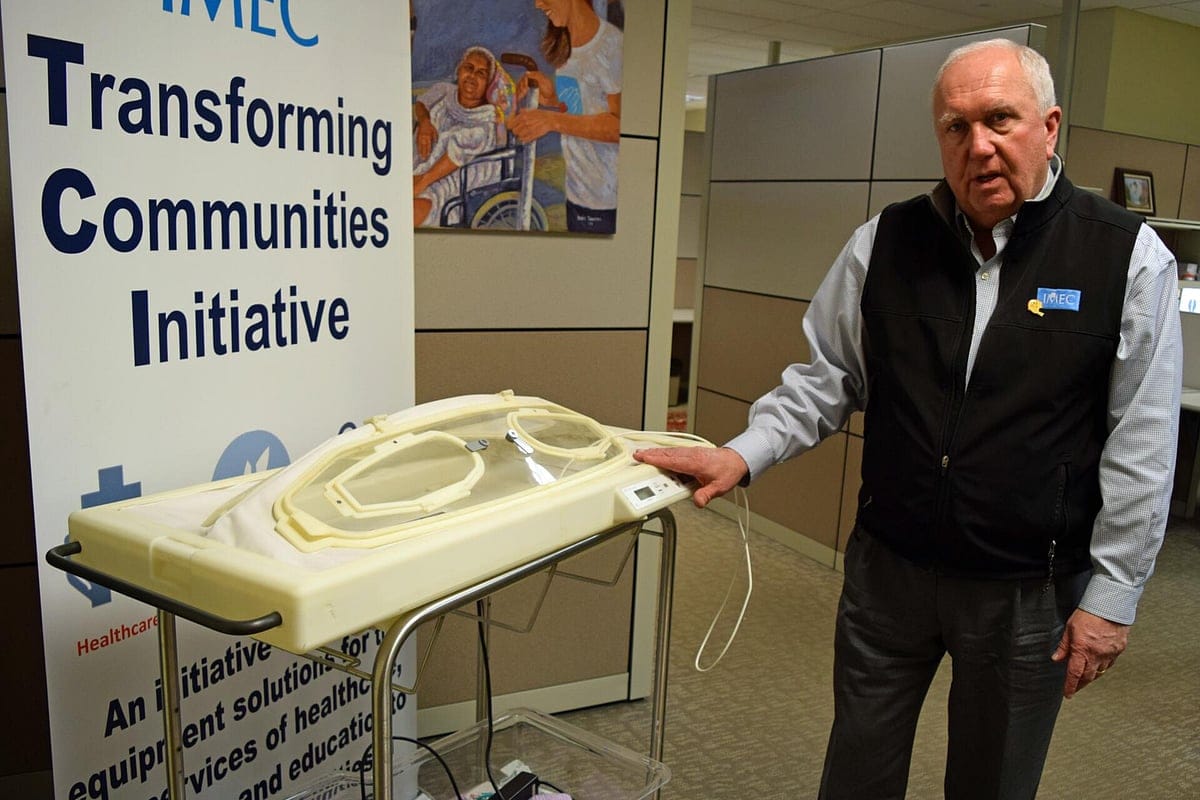

Twenty years ago, Tom Keefe left a career in hospital administration to turn his talents toward helping people in parts of the world that lack many basics taken for granted by most Americans, such as modern health-care facilities. Now he says the work of the organization he founded, known as IMEC, especially helps women and their children survive the rigors of living in less-advanced countries.