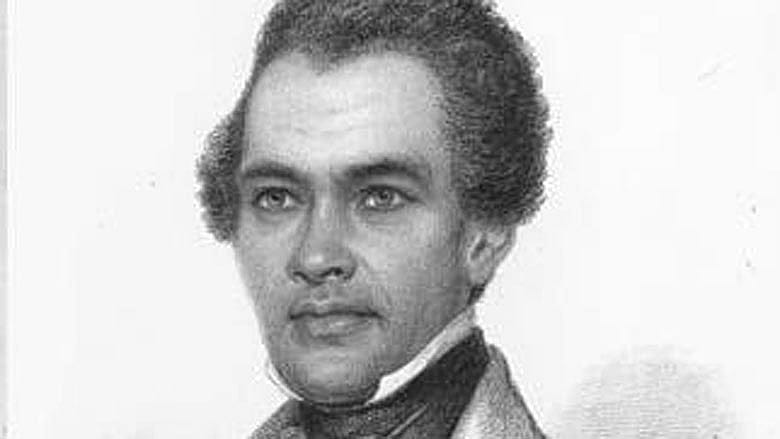

William Wells Brown’s intrepid journey as the first African-American playwright

After his dramatic escape from slavery, William Wells Brown (1814-1884) became the first published African-American playwright, and also the first to write a novel. His creative use of musical imagery in his stories had a powerful effect on his readers, and influenced other authors who imitated his technique. After many adventures, Brown settled down in Boston, and became a renowned abolitionist, lecturer, and historian.