Rape, rape culture, and reality

"Oops! I think I killed it." That was Robert Chambers squeaking in falsetto as he twisted the head off a Barbie doll in a home video. He was partying with four girls in their underwear when he was caught on the home video in 1987.

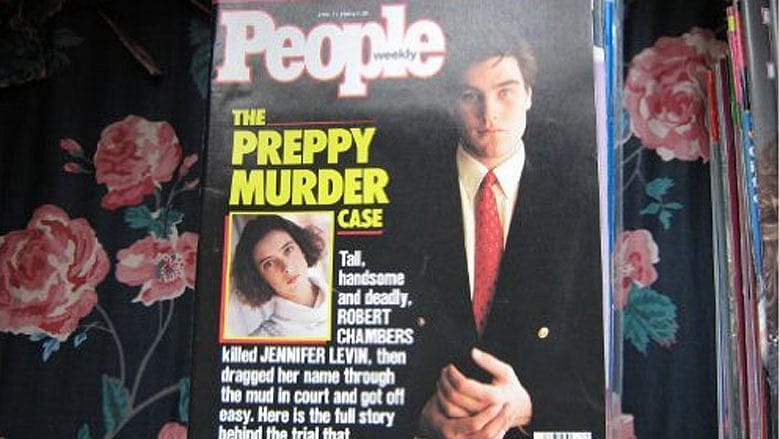

Robert Chambers? The name sticks if you were in Boston back then. Chambers, a one-semester Boston University drop-out, was known as "the Preppie Killer," the handsome young man who in August 1986 left the strangled, half-naked body of 18-year old Jennifer Levin on the ground behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.