Why soaring housing costs threaten Boston’s economic vitality

BOSTON – Boston is expensive. This shouldn't come as a surprise to anyone, but the numbers on the cost of living are enough to make even longtime residents consider relocating. According to Kiplinger, residing in Boston costs 39.7% more than the national average while health care and groceries are both about 26% higher. Yet median household income remains about the same as the rest of the nation and the city's poverty rate is a relatively high 21 percent.

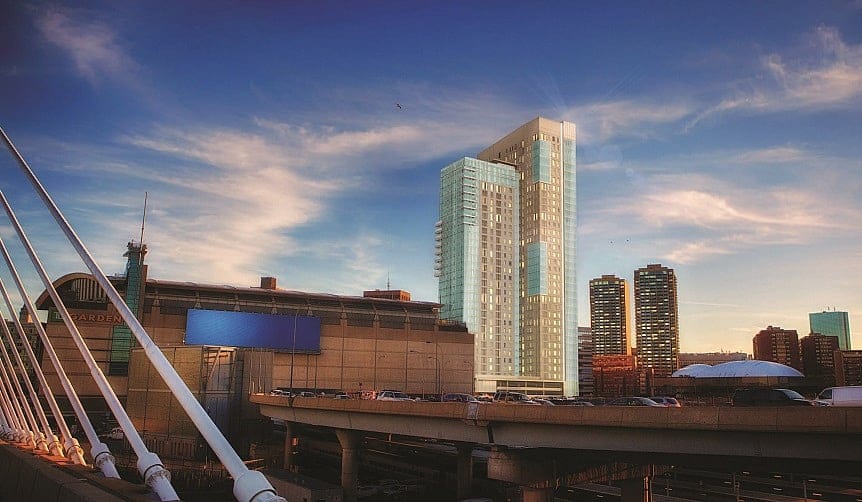

Why is living in Boston so expensive? Ask young people looking to live in the city or older folks hoping to return after an extended stay in the suburbs – Boston's housing market is terrifyingly pricey. Boston's population has been climbing for the past 20 years, rising almost 15 percent from 1990 to 2014, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Yet home construction in Greater Boston has lagged far behind, driving housing prices up, according to a November report from the Boston Foundation.