Book review: It’s Dangerous to Believe

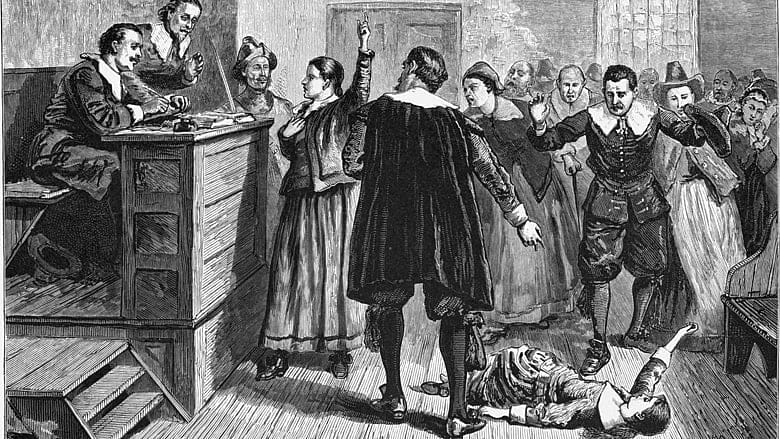

There's a new witch hunt underway. Occurring at the behest of an ascendant secular orthodoxy, the 21st century version is no less zealous in its fervor, its dogmatic absolutism, and its lack of concern for the evidence than the Puritan witch hunts of 17th century New England. Its victims? Small Christian colleges, faith-based homeschoolers, and Catholic charities, according to writer Mary Eberstadt.

In her new book, It's Dangerous to Believe: Religious Freedom and Its Enemies (Harper, 2016), Eberstadt argues that the long-running culture war over abortion and other kindred issues has, over the last decade, taken a sinister turn for the worse. In the past ten years, nuns have been forced by the federal government to include contraceptives in their health insurance offerings. Pastors in one of the country's largest cities have been ordered to submit any sermons on homosexuality or other gender-related matters to the mayor's office. Bakers have been sued and shamed out of business for refusing to provide wedding cakes at gay weddings, which now bear the imprimatur of state approval.