We Need a ‘Take Your Son to Work Day’

In 1993, Gloria Steinem and the Ms. Foundation for Women launched an event which was called "Take Our Daughters to Work Day." It was founded in order to expand the career horizons of young women. And its effect has been dramatic. In fact, the results were so explosive that within a short period, more women were attending college and university than men. In 2003, the name of the annual event was changed to Take Our Daughters and Sons to Work Day. But with the decline of men in the workplace, it is clear that we need an annual event named "Take Our Sons to Work Day."

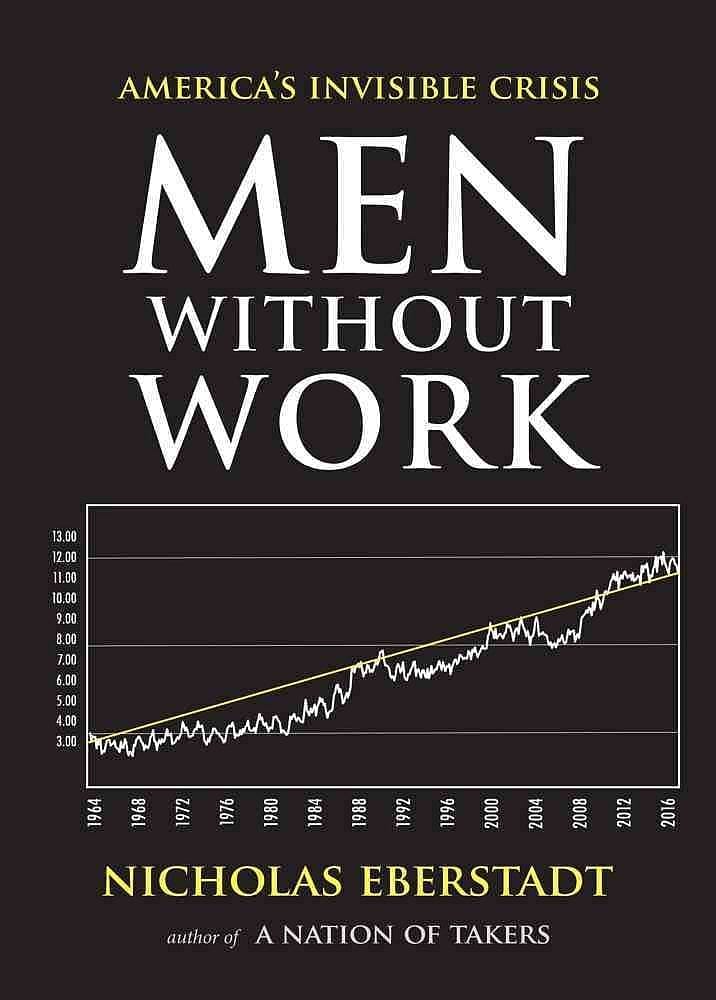

The astonishing absence of men in the U.S. workplace is the subject of a new book, Men Without Work, by Nicholas Eberstadt. In this short but compelling work, Eberstadt, who holds the Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute, documents that in 2015 nearly 22 percent of U.S. men between the ages of twenty and sixty-five were not engaged in work of any kind. The work rate for this group was nearly 12.5 percentage points below its 1948 level. Even more remarkable in a country where industriousness has always been prized as a virtue, a monthly average of nearly one in six prime-age men (ages 25 to 54) in 2015 had no paying job of any kind. In the 1960s, approximately 6 percent of prime-age men were not at work; currently more than 16 percent have no paid work in any given month. And even more worrisome is the fact that most of these men are not even looking for work.