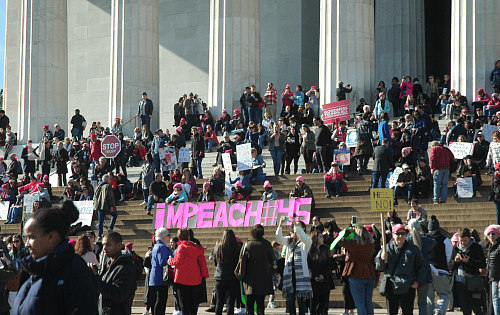

Democracy Teetering? Not As Long As Hierarchy Remains Intact

Fashionable circles like to see looming ahead of us the end of democracy. Pundits stoke this idea, often because their candidate didn't win office, and they were the ruling elites. The rumbling goes on because progressive ideas aren't the only ones afloat.

Freedom House publishes an annual report on political rights and civil liberties. This year it paints a sad picture of democracy in crisis. By their lights Russia, Turkey, Venezuela, Hungary, and Poland have scored setbacks. And the United States can't be far lagging.