Serving Their Country – in Normandy and Vietnam

It was truly inspirational to view the ceremony honoring some of the incredibly brave survivors of the June 6, 1944 D-Day assault on the beaches of Normandy. What tremendous courage and heroism! They deserve our everlasting thanks and gratitude.

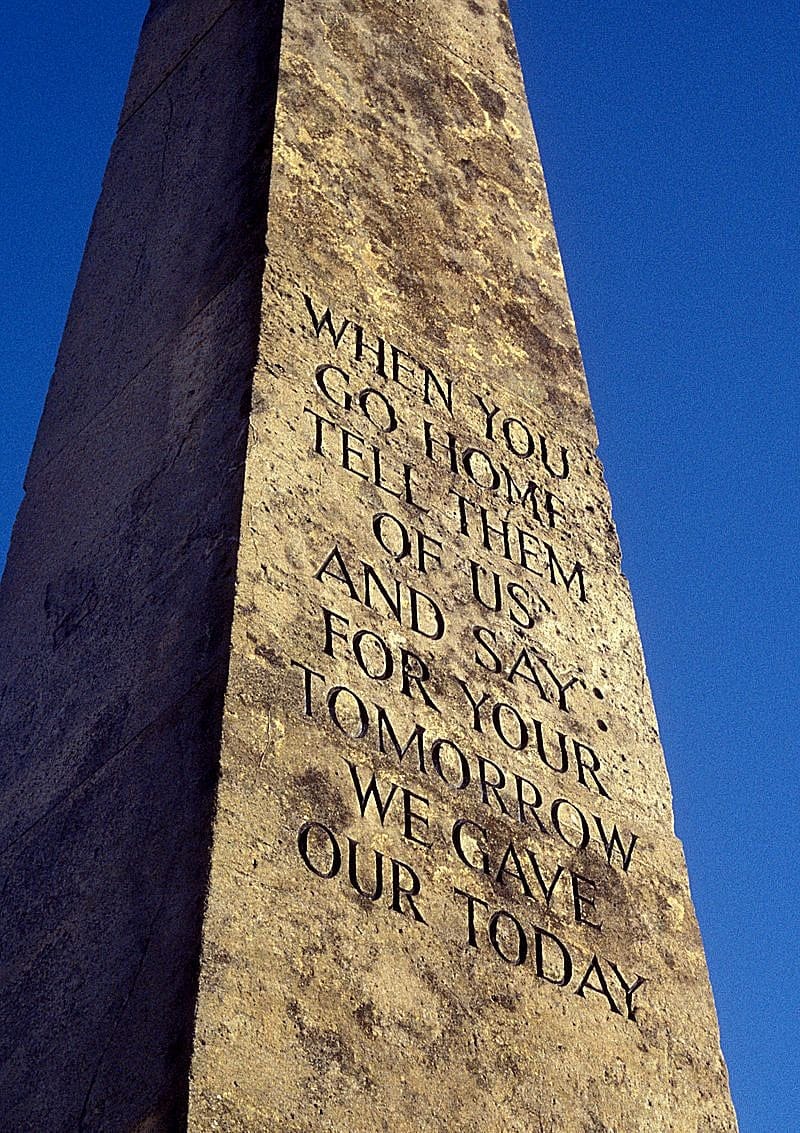

And then there are those who did not survive the assault – the thousands buried in the astonishingly beautiful U.S. cemeteries in Normandy. The words adorning a British World War II cemetery elsewhere surely apply to the thousands of heroes killed on the Normandy beaches: