Editorials

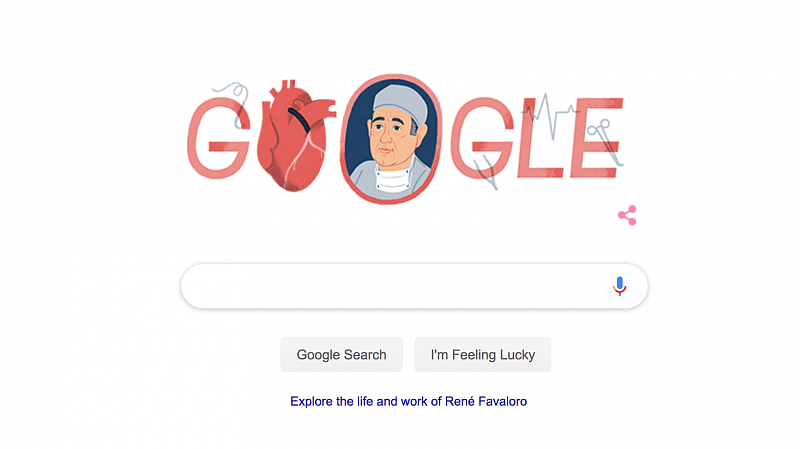

Foreigner’s Heart Bypass Breakthrough A Tribute To America of Old — But Don’t Tell Google

Google today is honoring an Argentinian doctor whose invention of the modern method for heart bypass surgery in 1967 took place in the United States.

Why is that? Why not in his native Argentina?