America Didn’t Just Happen; These Are Some of the People Who Made It What It Is

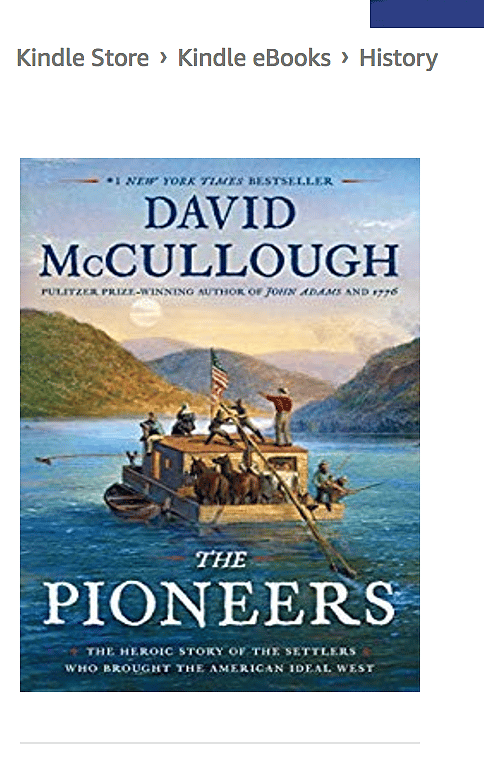

The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West

By David McCullough

Simon & Schuster

May 2019

352 pages

David McCullough has written another superb history, The Pioneers. Admittedly, it is not in the same class as his two magisterial biographies, Truman and John Adams, which would be difficult to match. But it is a wonderful recounting of a story largely unknown to most Americans – the settling of the Northwest Territory.