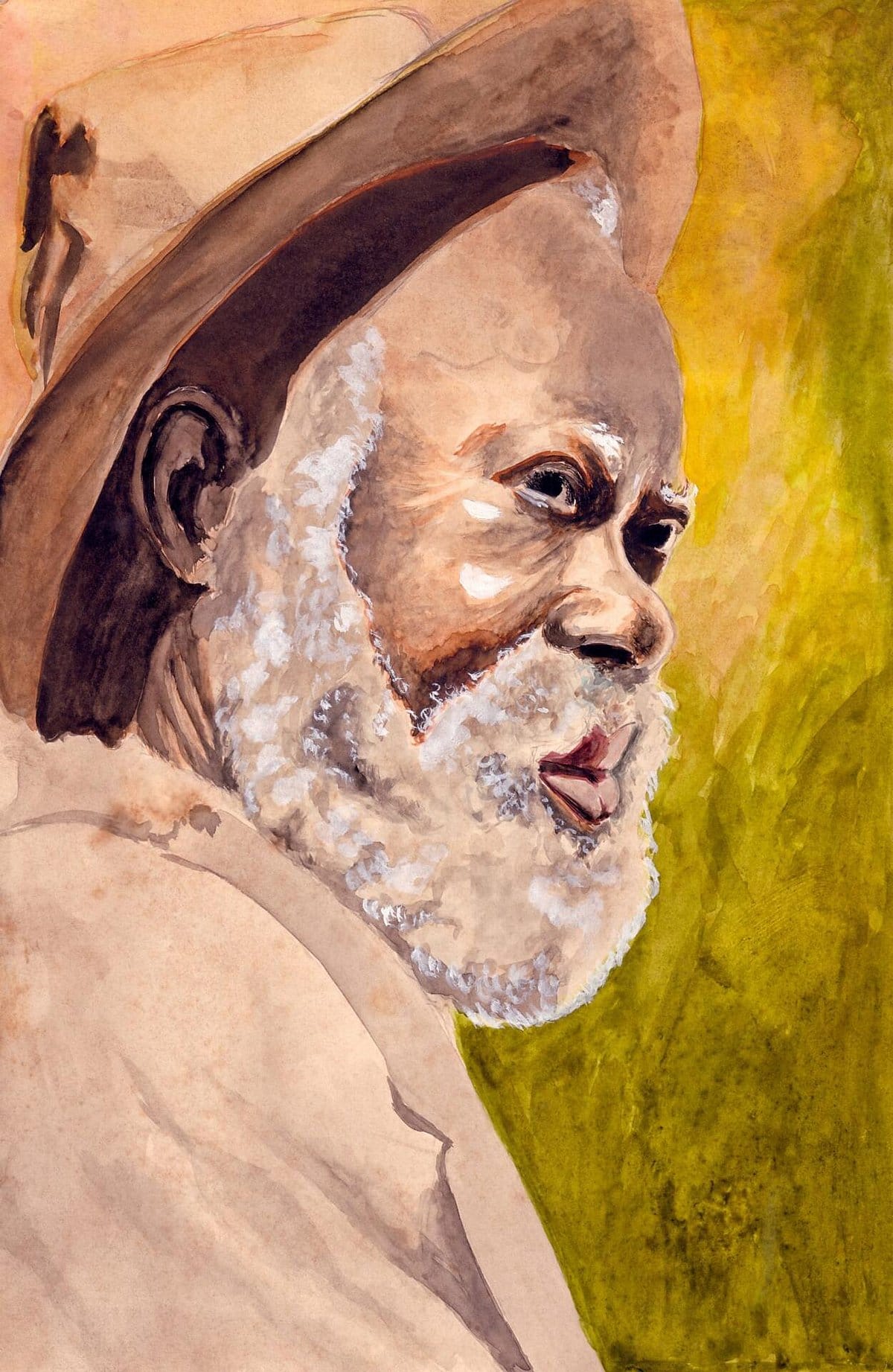

Celebrating Uncle Tom – He Isn’t Nearly What You Think He Is

In preparation for a talk on the life and import of Frederick Douglass, I was encouraged by my daughter, Katie, to read Uncle Tom's Cabin. Like many of us, I knew about the importance of Harriet Beecher Stowe's great novel in the cause of abolition of slavery. And I could even quote President Abraham Lincoln's perhaps apocryphal line when he greeted her in the White House, "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war. Sit down, please."

What I didn't know was that Uncle Tom's Cabin, first serialized in The Nation Era in 1851-1852 and published in book form in 1852, sold more copies than any book other than the Bible in 19th century America. It was also an international sensation, which was translated into 37 languages. It has never gone out of print.