Don’t Let Coronavirus Carry Off Our Culture, Too

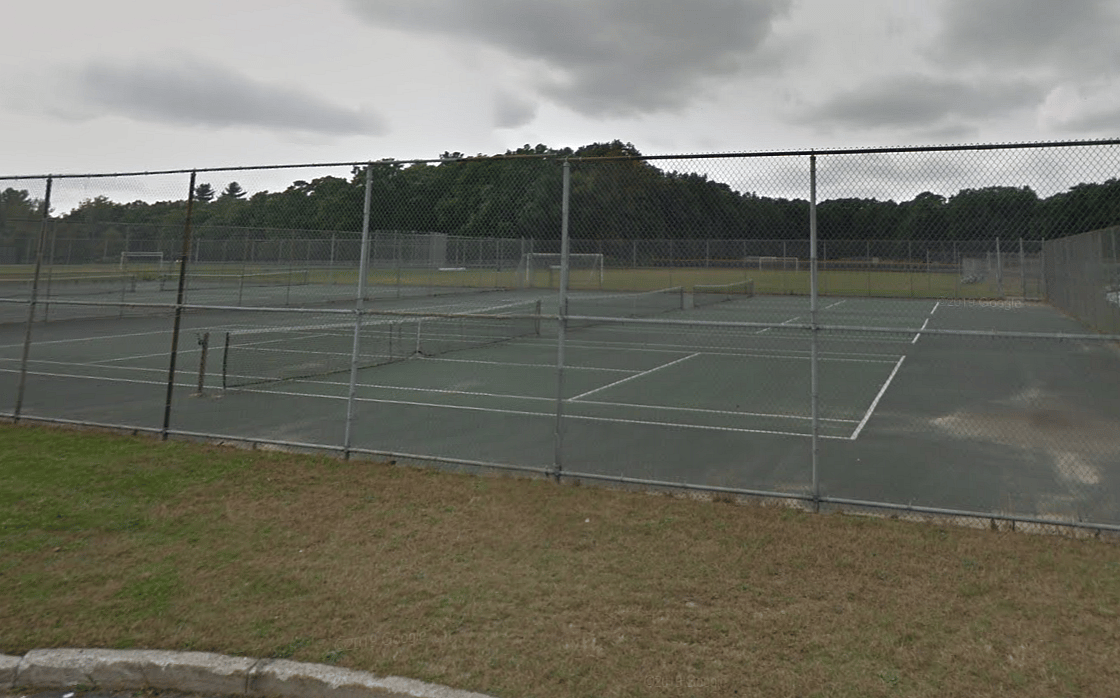

Many weekend afternoons, and some weekday evenings, every year from April through October, a group of people, young and old, male and female, black and white, advanced and beginner, meet to play tennis, shoot the breeze, trash talk, and sometimes share food and drink at our local park.

Our family of five has joined this group for the last twelve years, as a result of which my children have become avid tennis players and we have all become part of a community strong enough to fill a third of the church at the funeral of one of the group's founders a few months ago.