Commentary

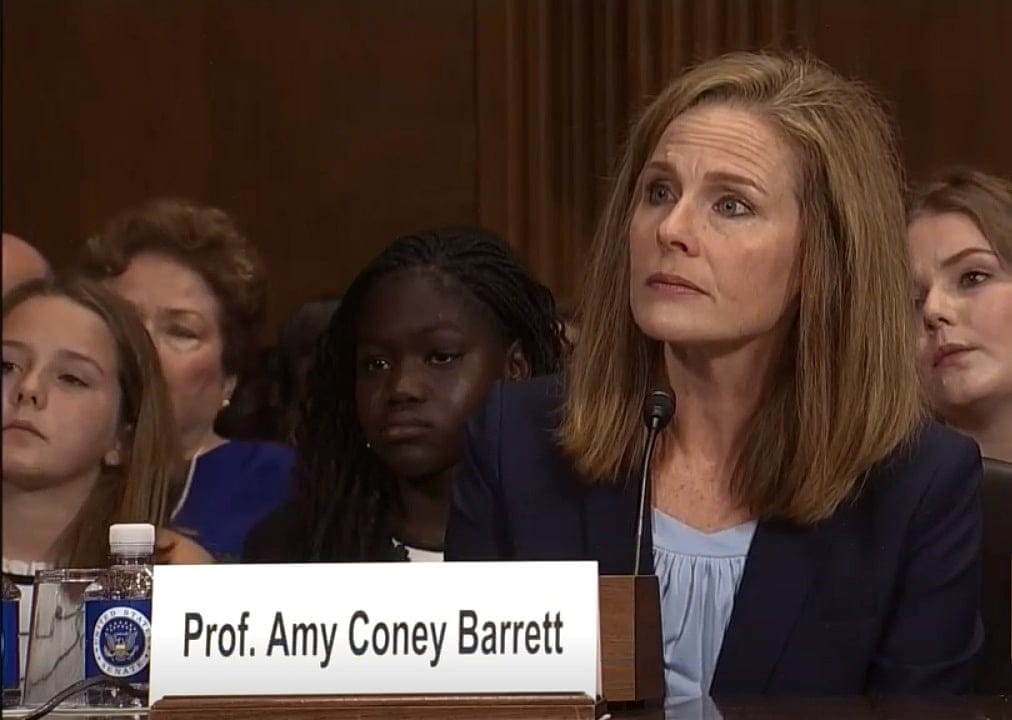

Amy Coney Barrett’s Religion Isn’t the Problem; It May Be Part of the Solution

"… reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle."

— George Washington, Farewell Address, 1796