“I know nothing”: Thwarting school choice in Massachusetts

One of the shortest-lived political parties in Massachusetts history pushed through a state constitutional amendment whose after-effects still bedevil us today. More than a century and one-half ago, the so-called Know Nothing party passed an amendment to prohibit any state funding for non-public schools, specifically targeting the burgeoning Irish-Catholic population in Boston and other large cities. Motivated by a deep anti-Catholic animus, the Know Nothings feared an influx of newly arriving families with children attending parochial schools.

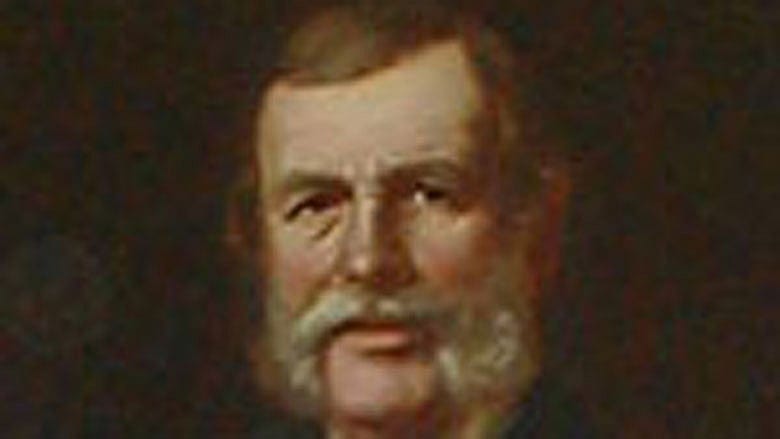

In an effort to shed light on the very different school choice question confronting families and educators today, the Pioneer Institute is calling upon Bay State political leaders to remove the portrait of a Know Nothing governor from "the top of the grand staircase, in a place of honor and prominence, at the entrance of the Massachusetts House of Representatives." The impressive portrait is that of Henry J. Gardner, thrice elected governor of the Commonwealth when terms lasted only one year.