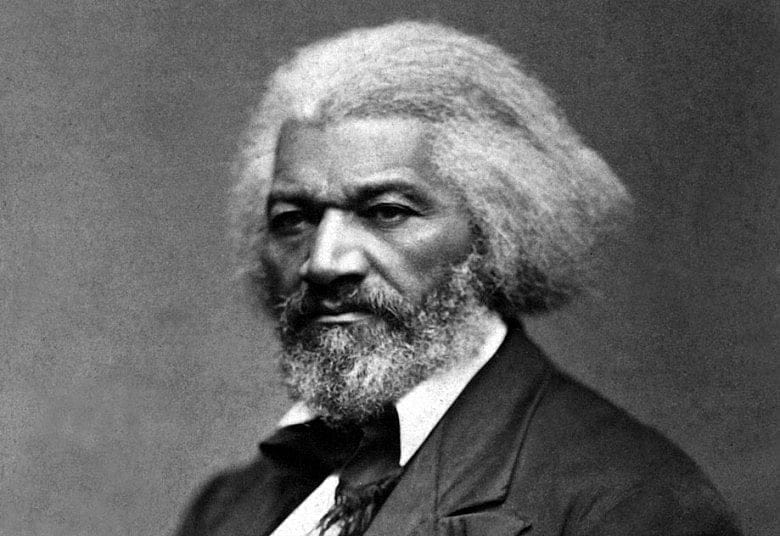

Frederick Douglass: Greatest African-American of the 19th Century

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

By David W. Blight

Simon & Schuster

October 2018

Frederick Douglass was the Martin Luther King Jr. of the 19th century. Former slave, author, orator, and statesman, Douglass was the principal black figure in the fight to abolish slavery. Over his long career, he became one of the best-known Americans of his day.