The Revolution Devours Its Father

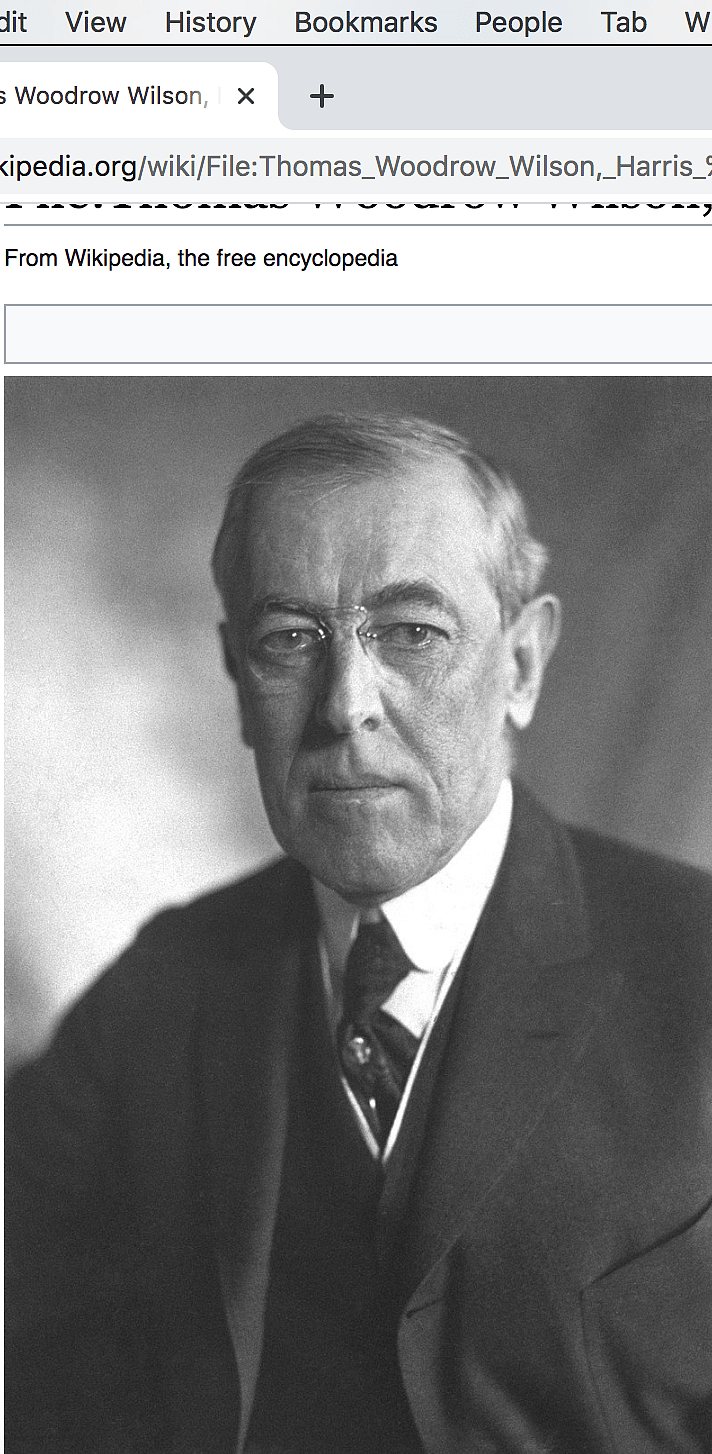

Left-wing demonstrators and rioters have managed to achieve in a matter of weeks what courteous conservative thinkers failed to accomplish in a century: Knock Woodrow Wilson off his progressive pedestal.

More than any other figure in American history, President Wilson embodied and popularized the 20th Century ideology known as Progressivism. Wilson's eight years in the presidency created the template for the modern administrative state: a powerful executive branch, an oversized bureaucracy, the increased centralization of government, an unending demand for so-called legislative reforms, and multiplying federal agencies regulating more aspects of life.