A Tale of Two Indians Shows How The West Was Really Won – Tecumseh and The Prophet

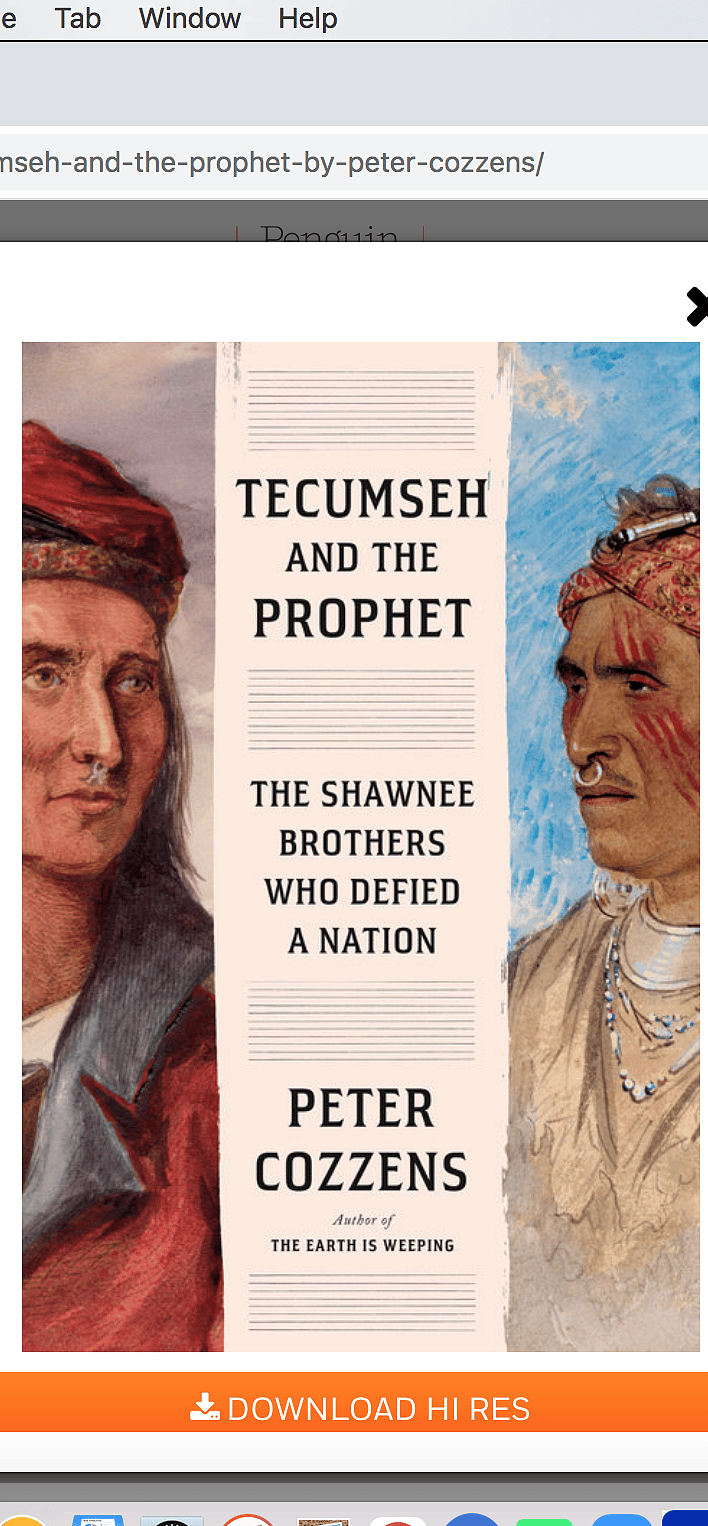

Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied A Nation

By Peter Cozzens

Knopf

October 2020

560 pages

In Tecumseh and the Prophet, Peter Cozzens, formerly a captain in the U.S. Army and later a foreign service officer, has written a frank and unvarnished account of the struggle between the two million or more white colonial settlers and sixty thousand Native Americans in the five states that made up the original 1787 Northwest Ordinance territory – Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin.