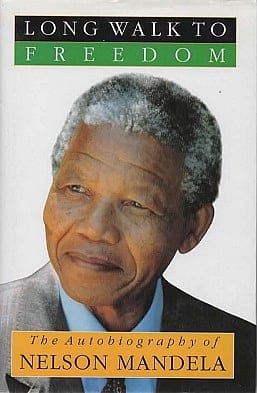

South Africa Avoided Civil War Through One Man’s Forgiveness – Book Review of Nelson Mandela’s Long Road to Freedom

Recently, I watched the DVD of the 2009 movie Invictus. Starring Morgan Freeman as Nelson Mandela, and Matt Damon as captain of the South African rugby team, and directed by Clint Eastwood, it is a marvelous movie. It tells the story of how South African President Mandela hosted the 1995 World Cup of Rugby and cannily used the Springboks rugby team to knit the 43 million inhabitants of South Africa together into one nation – despite the decades of bitterness and hatred caused by apartheid.

My wife and I lived in Johannesburg, South Africa from 1972 to 1974 when I was working for Citibank, and our first daughter was born there. I spent many afternoons in Ellis Park, Johannesburg – the stadium where the South Africa rugby team, the Springboks, later defeated the New Zealand All Blacks before 62,000 spectators in the finals of the World Cup in 1995. Seeing the movie (for the second time) inspired me to read Nelson Mandela's autobiography, Long Road to Freedom.