When religious fashion invites suspicion

By Suzanne Fields | December 12, 2015, 5:00 EST

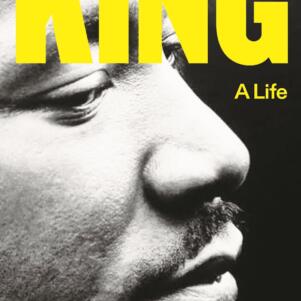

(Courtesy of Flickr)

(Courtesy of Flickr) When I was a girl, graduating from Old Testament and Hebrew language studies at a conservative synagogue, I wore a white robe, carried an armful of red roses and gave a speech to my family and the congregation. A wealthy friend of the family, an orthodox member of the faith, sent me a necklace with a pendant and a 2-carat diamond set in a platinum six-pointed Star of David.

I never wore it, though I appreciated the gift and the spirit of the gesture. But even as a girl I was not comfortable wearing religious items of identification. Maybe it was the Holocaust, fresh in the memory and consciousness of everyone, that made me wary of identification. Or the Star of David with a diamond might be seen as ostentatious, suggesting the stereotype of Jewish wealth and privilege. For whatever the reason, I’ve never been comfortable with religious jewelry.

Many Christian women wear the cross as a pendant, though many Christian women, especially Protestants, are offended by the idea of wearing the cross as jewelry. The cross is sometimes worn in other countries, particularly in Asia, only as jewelry, by young women ignorant of the significance of the cross. But Muslims are the most predominant group to practice public identification of religious belief. They have established Muslim garb as fashion. Luxury stores such as Harrods in London, KaDeWe in Berlin, Printemps in Paris and Bergdorf Goodman in New York City display colorful and decorative head scarves, or hijabs, of cotton, wool, polyester and fine silk.

The long black chador is associated with devout Muslims, but not always. Recently I saw many Muslim women in Berlin covering themselves in the chador in the street, and in a German home they took off their dark outer garments to reveal Western jeans and colorful sweaters and T-shirts. This is the custom of recent refugees as well as children of Turkish families who have been in Berlin since before the Wall fell.

Fashion meets religious symbolism as savvy retailers quickly learn to turn cultural attitudes into trade. I once wondered, in a macabre “what if” fantasy, whether Hitler and the Nazis could have killed 6 million Jews if everyone had worn the yellow armband prescribed for only the Jews.

Now that the face of Tashfeen Malik, framed in a black hijab, has been on every front page, on every television screen and splashed across the Internet, will the chador, the hijab, invite suspicion, mistrust and apprehension in airports, train stations and other public spaces where everyone feels vulnerable to terrorists?

The most patronizing part of President Obama’s Sunday night speech was the way he implored everyone to reject religious prejudice, as if that’s the problem. Religious prejudice is not a widespread problem in America or Europe, even though bigotry exists in pockets throughout the world, as it always has. Donald Trump’s demand for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,” elicited angry rejections among Republicans and Democrats across the board, from Dick Cheney to Hillary Clinton.

But only the foolish say they have no fear of terrorists among us, who often come dressed in black. Until San Bernardino, nearly everyone kept their fears to themselves, some remembering how Juan Williams, whose civil rights credentials are impeccable, lost his job as a commentator on National Public Radio for telling interviewer Bill O’Reilly that “when I get on a plane, I’ve got to tell you, if I see people who are in Muslim garb, and I think, you know, they are identifying themselves first and foremost as Muslims, I get worried. I get nervous.” He was expressing the unspoken sentiment of nearly everyone, including the executives at NPR who sacked him.

America is not a nation of bigots, but when people are frightened they sometimes look for protection in the wrong places. Sometimes their fear of being unfair leads them to say nothing when they should say something.

One of the most chilling stories to come out of the San Bernardino massacre was about how neighbors of the terrorist couple, suspicious of the large number of packages being delivered to their house and how the couple spent long hours in their closed garage, wouldn’t call the cops. They said later they didn’t want to be accused of “racial profiling.”

We must all be wary of suspicious activity. FBI director James Comey warns everyone, “If you see something, say something.” If the neighbors of the San Bernardino killers who saw something had said something there might have been no massacre. It’s a sad commentary on the times we live in that religious symbolism, once held in holy regard by nearly everyone, has become the object of suspicion — sad, but necessary.

Suzanne Fields is currently working on a book that will revisit John Milton’s ”Paradise Lost.” Write to her at [email protected], and read her past columns here.