Getting to the heart of the matter: Dr. DeSanctis listens with more than just his stethoscope

By Diane Kilgore | February 19, 2016, 10:27 EST

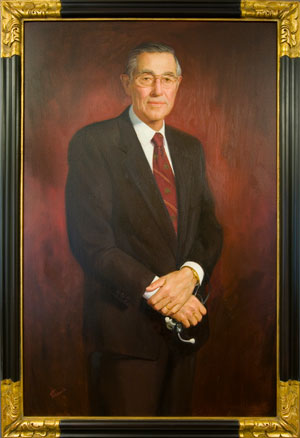

Dr. Roman DeSanctis (Courtesy photo)

Dr. Roman DeSanctis (Courtesy photo) Dr. Roman DeSanctis is a medical Hall of Famer. Practicing cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital for more than 60 years, he’s treated kings, political emissaries, movie stars, professional athletes, and one very special lady from Chelsea who told him dirty jokes until he had to laugh out loud.

DeSanctis, who believes in faith, miracles and tender mercies, also believes in sitting on the soft bedside of patients when delivering hard news. As Director of Clinical Cardiology Emeritus, DeSanctis teaches Harvard Medical School students to hold the hands of patients and look into their eyes to see the heart of those they’re treating. Rather than rely exclusively on science, DeSanctis encourages cardiology residents and Fellows to listen carefully, beyond the murmurs, to what matters most to their patients. This man of the Old West loathes cold winters but loves the warm hearts of New Englanders as he employs kindness and compassion; espousing humanity not technology as the corner stone of medical care.

Calling for by-passes, redesigning cardiac walls, syncing the beat of a heart that’s lost its rhythm, DeSanctis is to cardiology what Tom Brady is to football, what I.M.Pei is to architecture, what Billy Joel is to rock and roll. The medical legend with a photographic memory pauses and calls himself corny, sometimes pedantic, reflecting on the value of a pat on the back, a sincere hug and his perpetual habit of making time for kindness. “Because of his empathetic care of patients, Roman has been arguably the premier cardiologist in this country” said Dr. W. Gerald Austin, former chief of surgical services at MGH to staffers upon DeSanctis’ retirement from full-time practice in 2014.

Dr. Adolf Hutter Jr., Director of the Cardiac Performance Program at Mass General, said to on-lookers at the 2006 unveiling of a portrait commissioned in honor of DeSanctis, he believes DeSanctis’ impact on how cardiology should be practiced “will be felt for generations of cardiologists.” The doctor is “a master clinician, teacher, and mentor who, along with Dr. Paul Dudley White, has defined cardiology at MGH over the years.” White, who passed away in 1973, is considered the father of preventative cardiology.

One of Boston’s All-Star cardiologists almost didn’t make it to the Boston area. A cynical admissions board member at Harvard Medical School was persuaded not to scratch DeSanctis’ application to the class of 1955. The board member, a psychiatrist, wasn’t convinced the summa cum laude graduate of the University of Arizona would add much to the incoming class of Ivy graduates.

As a medical student, DeSanctis distinguished himself, treating patients with heartfelt, unfailing scientific excellence while enthusiastically embracing the vision of his mentor, White. White’s research showed eating a low-fat diet, controlling cholesterol, blood pressure, body weight and sugars are the path to wellness.

Among other associations, he and students organized the Framingham Heart Study that focused on the role of genetics in coronary artery disease and the merits of returning to an active life soon after a heart attack. White was such an optimistic proponent of physical activity that Boston honored him with a multi-use bike path along Storrow Drive that bears his name.

Symbolic recognition of White’s contribution to cardiology loops around the heart of the city perpetually reminding travelers of his gifts and the cycle of life. His brilliant mind mentored protégés, like DeSanctis, who then taught doctors around the world how to listen to a patient’s heart with more than just a stethoscope.

Building on the lessons of those two legends, patients rely on care from an All-Star band of cardiologists practicing in and around Boston today. Of those rock stars, none advance the tone of White and DeSanctis opus with more clarity than James Januzzi. Januzzi practices cardiology at Mass General Hospital. He was the first incumbent of the Roman W. DeSanctis Endowed Distinguished Clinical Scholar in Medicine Chair. Presently, he’s the Hutter Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He’s an active clinician, a prolific researcher, and has been the cardiac consultant to the Red Sox since 2005.

Januzzi, who graduated first in his class from New York Medical College in 1994, credits his father for some of his success. As a child, he frequently accompanied his dad, a gastroenterologist, to work. There he became familiar with the sights and sounds of a hospital and saw how his father’s hard work mattered in the lives of his patients. Januzzi has left a lasting bio-mark on advancements in medicine. As a respected researcher, two of his 400 publications in particular speak to the passions of his predecessors. One article quantified the beneficial properties of an optimistic disposition in patients with coronary artery disease; the other studied blood markers that reliably predict complications after some surgeries.

Januzzi is considered by his peers to be a gifted physician, professor,and medical visionary. Where this man further distinguishes himself is as a humanitarian. He took the Hippocratic Oath ” First Do No Harm” beyond its mandate. Before he picks up his stethoscope, he listens with attention and compassion to his patients as they pour out their hearts. Like his father, and the doctors who have mentored this virtuoso’s talents, Januzzi cares for and about his patients.

As an active clinician and professor, Januzzi ensures his capable students are medically proficient and meet the ever-increasing demands of their profession. Sadly, he says, some of them wear a cavalier air over their lab coats, satisfied by the appearance of looking smart. Many are afraid of drowning under paperwork and rush through appointments, taking electronic notes on iPads, seldom looking up, seeing only the virtual light of patient care.

The students he admires most are the scholars who also make time to sit on the soft bedside of a patient who heard bad news. He says those few shine with an innate spark of humanity. For them, he believes medicine will be far more than a job, it will be a lifetime of giving and receiving rewards of its noble calling.

Januzzi, like his mentor DeSanctis, and like White before him, teaches that it’s the personal touch — listening to a patient, being empathetic and sometimes, even hearing out the occasional little old lady who wants to tell dirty jokes — that makes a difference.