Boston immigrants drive Hub’s economic vitality, author says

By Kara Bettis | March 10, 2016, 18:12 EST

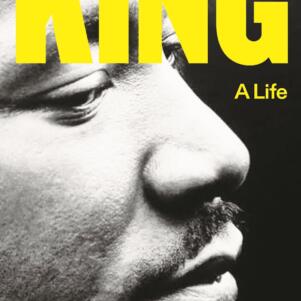

Boston College historian Marilynn Johnson speaks about the importance of immigrants to the city’s economic vitality. (New Boston Post photo by Kara Bettis)

Boston College historian Marilynn Johnson speaks about the importance of immigrants to the city’s economic vitality. (New Boston Post photo by Kara Bettis) BOSTON – Immigrants are more central than ever to Boston’s economy. They make up more than a quarter of city residents and spend around $4 billion annually, which accounts for almost 26,000 jobs and generates $1.3 billion in tax revenue, according to the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

But one of the major influences in the development of Boston – which is home to the sixth-largest proportion of foreign-born residents among U.S. cities – over the past several decades is immigration, argues Marilynn Johnson, who teaches history at Boston College.

Johnson is the author of seven books, including “The New Bostonians: How immigrants have transformed the metro area since the 1960s,” her latest. The work explores the positive impact of newcomers to America on the Hub’s economic and cultural progress in the past half-century, since President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1965 Immigration Act.

The author explored the topic with an intimate and diverse gathering at the Massachusetts Historical Society on Wednesday.

While the most commonly acknowledged effect of immigrants is their contribution to the local labor force, Johnson said entrepreneurship and cultural contributions are also significant when it comes to Boston’s foreign-born residents.

Between 1950 and the end of the 1960s, Johnson wrote in a Boston Globe article last year, the city lost more than 20 percent of its population and about 40 percent of its manufacturing jobs. That led to increases in “rundown housing, deteriorating schools, vacant storefronts, and neighborhoods scarred by urban renewal and growing racial tensions.”

And, while many feared in those days that widening the door to immigrants “would make matters worse,” the legislation LBJ signed was actually a “a critical turning point” that led to a boom in population and economic stabilization, she wrote.

In her comments Wednesday, she pointed out that immigrants can be found in occupations that span the economic spectrum – from well-paying jobs in high-technology industries and medicine to low-paid work in services.

Changes that began in the final years of the 20th century were radical, she said. For one thing, Boston’s immigrant population began to balloon, expanding 46 percent from 1990 to 2010, the BRA data show.

Johnson said Boston’s Chinatown provides an example of the magnitude of change. The neighborhood once bordered the city’s “Combat Zone,” a several-block area centered on Washington Street and strewn with adult book and video stores and strip clubs. Starting in the 1980s, the area began to evolve and has become a flourishing center for Asian cuisine and high-rise apartment buildings as Vietnamese immigrants and refugees settled in the neighborhood.

Although changing policies and gentrification certainly catalyzed change, “without these entrepreneurs who first were willing to go in and take some risks and open up small businesses, it probably would not have happened as quickly or in the same way,” Johnson said.

Similar changes can be found in parts of Dorchester, East Boston, Allston-Brighton and other neighborhoods, she said.

Now, due to the soaring cost of living in Boston proper, many immigrant communities have migrated to more affordable suburban areas. There, she said, they are also aiding the renewal of those cities and towns, such as Framingham, Malden and Quincy, among many others.

In addition to economic shifts, the growth of foreign-born populations has led to cultural, political and religious evolution. The Korean Church of Boston, for example, is now located in a spacious Brookline church that once housed the mostly American-born members of the First Presbyterian Church of Boston.

“This is not an entirely rosy account,” Johnson concluded. “For all the good that immigration has done for the Boston area, there have been conflicts, there have been dislocations, there has been persistent discrimination.”

Lack of affordable housing in the metropolitan area and quality education for the children of immigrants and refugees are among the key challenges new arrivals still face.

Johnson said the city needs to tackle these problems.

“As the baby boom generation will be retiring in the next 10-15 years, we will need immigrants and their children to replace all of these lost workers who will be retiring. Immigrants will need the education and skills necessary to take our places and participate in the new knowledge economy that’s now a way of life in Boston.”

Contact Kara Bettis at [email protected] or on Twitter @karabettis.

NBPUrban