Hawaiians Journey to Park Street Church to Celebrate Commissioning of First Missionaries to Their Islands in 1819

By Robert Bradley | October 30, 2019, 17:19 EDT

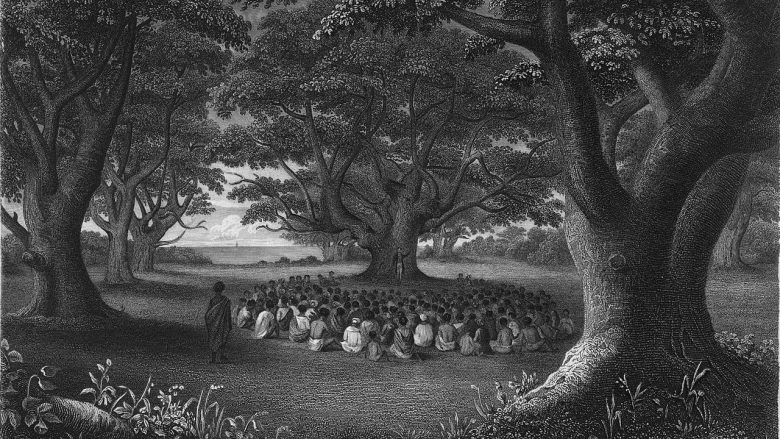

A New England missionary preaches in a kukui grove in Hawai’i, as depicted in an engraving appearing in Wilkes’s Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition. Drawn by Alfred T. Agate. Engraved by Rolph, J. A. — David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

A New England missionary preaches in a kukui grove in Hawai’i, as depicted in an engraving appearing in Wilkes’s Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition. Drawn by Alfred T. Agate. Engraved by Rolph, J. A. — David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Courtesy of Wikipedia. Last week, over 100 Hawaiians flew to Boston to commemorate the commissioning of missionaries at historic Park Street Church two hundred years ago. Many Hawaiians leaders made the journey. Peter Young, the great-great-grandson of the mission’s leader, Hiram Bingham, played a key role in the celebration at the church last Wednesday. The program also included Hawaiian music and hymns, some performed by Timberlane Regional High School in Plaistow, New Hampshire.

Contradicting the prevalent myth that dour and bigoted Christian missionaries to the Sandwich Islands destroyed Hawaiian culture, the Hawaiians, who travelled to Boston to take part in the celebrations, went out of their way to emphasize the many beneficial changes that the missionaries introduced to Hawaii. For example, the first missionaries, with help from native Hawaiians and support from the rulers, created the written Hawaiian language and translated the Bible into Hawaiian. The missionaries established the first school during their first year in Hawaii. They eventually helped to found nine hundred schools, which led to an astonishingly high Hawaiian literacy rate of 95% within several decades of the missionaries’ arrival in 1820.

The positive legacy of the missionaries is one of the reasons why Hawaiian Airlines was an official sponsor of events in New England held by the Hawaii Mission Houses Museum and Archives.

Park Street Church staff and volunteers organized a weeklong celebration for their Hawaiian brothers and sisters. The main event was a program at the church that took place two hundred years to the day from when the missionaries boarded the Thaddeus at Long Wharf in the Boston Harbor on October 23, 1819.

The program on Wednesday, October 23 was punctuated by a theatrical performance My Name is Opukaha’ia. Moses Goods staged a dazzling one-man play depicting the life of Opukaha’ia (called Henry Obookiah by New Englanders 200 years ago) – a Hawaiian orphan who came to New England in 1809. His tragic life in Hawaii, his desire to come to America, his conversion to Christianity, his strong character, and his desire to bring the gospel to Hawaii were largely responsible for the growing interest among New England churches to send missionaries to the Sandwich Islands (as they were known at the time). The description below of Opukaha’ia and his life is taken largely from Christopher Cook’s superb book, The Providential Life and Heritage of Henry Obookiah.

Opukaha’ia’s Early Years

Born and raised on the big island, Hawaii, Opukaha’ia and his family were caught up in savage tribal warfare. At age 10, Opukaha’ia witnessed the brutal murder of his mother and father by warriors from another tribe. Snatching up his younger brother and carrying him on his back, he ran for his life. A warrior chased after them, and a knife aimed at Opukaha’ia killed his baby brother instead. Captured by the warrior, Opukaha’ia was brought to the triumphant chief, who spared his life. Adopted by a kind family, he was brought up to be a priest in Hawaii’s pagan religion, but, shunning this life, Opukaha’ia swam to an American brig, Triumph, and asked to join the crew.

Triumph was captained by Caleb Brintnall. Brintnall, a devout Christian, agreed to take Opukaha’ia and another Hawaiian boy named Hopu (age 12) on the Triumph as part of his crew. After sailing the Pacific for months and trading seal skins in Canton, China, the Triumph made the five-month voyage back to New York, where Brintnall sold his goods and his ship and paid off the crew. He then invited Opukaha’ia to return with him to New Haven, Connecticut and stay at his home. Opukaha’ia was twenty years old and was soon bewildered by life in New Haven.

Samuel Mills and the Second Great Awakening

In the fall of 1809, a Yale student, Edwin Dwight, found Opukaha’ia crying on the steps of Yale’s main gate. When Dwight asked him what the matter was, Opukaha’ia told him that no one would help him learn. Dwight took him under his wing and introduced him to his relative, Timothy Dwight, who was the president of Yale College. With this act of Christian kindness, Opukaha’ia was on his way to learning English and beginning his pursuit of knowledge.

It was at this time that he met Samuel Mills. Mills had matriculated at Williams College and was a leader in a group of evangelical students there who called themselves the Society of Brethren. This was in the early days of the Second Great Awakening, which culminated several decades later under the leadership of Charles Finney. One summer afternoon, six of the Society of Brethren including Samuel Mills met in a grove of maple trees to pray, and being caught by a thunderstorm, they sought refuge in a nearby haystack. It was there, near the spot where the Haystack Monument now stands, that six Williams students committed themselves to foreign missionary service. Some years later, through their efforts and those of many graduates from other colleges who studied at Andover Theological Seminary, Congregational churches throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut were inspired to launch the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.

Following his graduation from Williams, Samuel Mills went to Yale for a semester of graduate theological study and also to recruit students for membership in the Society of Brethren. Mills took Opukaha’ia under his wing and began to mentor him. Then, he invited him to move with him to his family home in Torringford, Connecticut, which is in Litchfield County. Opukaha’ia made the trip with Mills and was welcomed into the Mills home as a family member. Over the next years, Mills became like a brother to Opukaha’ia. When Mills departed for Andover Theological Seminary to get his degree to become a minister, Opukaha’ia stayed with the Mills family to continue his walk in the Christian path and further his studies. Later he, too, went to Andover and then to Bradford to continue his formal education.

Opukaha’ia’s Vision to Bring the Gospel to Hawaii

Returning to the Mills home in Torringford in 1813, Opukaha’ia’s vision for bringing the Gospel of Jesus Christ back to Hawaii began to take root. In 1814, the first short biography of Opukaha’ia’s life was written and circulated among Congregational churches in Connecticut, and this created great enthusiasm about a mission to Hawaii. In 1815, Pastor Harvey delivered an influential sermon at the annual meeting of the Foreign Mission Society of Litchfield, and Goshen, where Opukaha’ia was staying, sent a formal request to the American Board of Commissioners for a mission to the Sandwich Islands.

In 1815, Samuel Mills’s father, an influential pastor in Connecticut, baptized Opukaha’ia in Torringford. For the next several years, Opukaha’ia, together with several other Hawaiians, toured dozens of churches, casting a vision of missionaries bringing the gospel to Hawaii. His strong personality and fervent prayers created great enthusiasm for this endeavor. To help achieve this goal, a Foreign Missions School was established in Cornwall, Connecticut, where Opukaha’ia became the star pupil. In 1818, a review of his life was published in the Missionary Herald describing his growth as a Christian.

But then tragedy struck. Opukaha’ia contracted typhus. He fought bravely against the disease, firm in his Christian conviction. Little did he know that his brother, Samuel Mills, who was on a ship off the coast of West Africa, evaluating the possibility of a mission, was also dying. Despite every effort to save his life, Opukaha’ia died in Cornwall, Connecticut in the late winter of 1818. Mills died in May 1818 of consumption.

Shortly after Opukaha’ia’s death, Edwin Dwight, who had befriended him on the steps of the gate at Yale, compiled a small memorial volume entitled the Memoirs of Henry Obookiah. The biography of an orphan turned pagan priest turned evangelical scholar and preacher created enormous enthusiasm for a mission to the Sandwich Islands.

Thus, one can understand the comment last week by Peter Young, the great-great-grandson of Hiram Bingham, the leader of the first mission to Hawaii, that he attributed his very existence to the influence and life of Opukaha’ia. Without him, there would have been no mission to Hawaii.

The Thaddeus Sails for Hawaii in October 1819

The ordination of Hiram Bingham and Asa Thurston as missionaries to the Sandwich Islands was celebrated at the Congregational Church in Goshen in September 1819 – less than a month before their planned departure from Boston. However, the American Board of Commissioners established a critical condition before they could journey to Hawaii: they must marry. They had three weeks to find wives.

Both (quickly) found pious and adventurous women, and they were married shortly before the Thaddeus departed for Hawaii. With the departure date set for October 23, 1819, a weekend celebration for the first group of missionaries to the Sandwich Islands was planned at Park Street Church in Boston. The group consisted of four native Hawaiians, seven couples, and five children. Before the Friday evening service, the missionaries and their companions signed a written covenant much like the Mayflower Compact. At the church service that night, which more than 500 attended, Hiram Bingham preached the sermon. At the Sunday communion service, Asa Thurston preached, and Thomas Hopu, the Hawaiian who had joined Opukaha’ia years before as a member of the crew on the Triumph, gave the benediction in the Hawaiian language. On October 23, 1819, the group assembled on Long Wharf where the 85-foot brig Thaddeus was moored at the pier. Nearly six months later, on March 30, 1820, they arrived safely in Hawaii.

In Hawaii, Fertile Soil when the Missionaries Arrive

Providentially, the situation in Hawaii could not have been more favorable when the Thaddeus arrived. During the previous several decades, the Sandwich Islands had been unified by King Kamehameha I. In 1819, the year before the missionaries arrived, the royal family had ended the kapu system – the religious law system in the Sandwich Islands that ruled over all acts and behavior in Hawaiian life. Previously, an offense against kapu usually meant the death penalty. Moreover, human sacrifice had been prevalent. The Hawaiian leaders had also decided to destroy their idols. Far from the caricature of the missionaries in James Michener’s deeply unfair novel Hawaii, the missionaries were a blessing to the Hawaiians. They arrived at a propitious time when the royalty and tribal chiefs welcomed the missionaries and their Christian beliefs, and they willingly assisted in the implementation of the Christian worldview. With the creation of the written Hawaiian language, the translation into Hawaiian of the Bible and the widespread emphasis on education, the missionaries created a fruitful environment that benefited the Hawaiian people and changed the face of Hawaii in a positive way.

Park Street Church’s Missions Program

The visit of more than 100 Hawaiians to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the commissioning of the first group of missionaries reflected how much fruit has been harvested from this spiritual outreach. The visit was a great blessing to Park Street Church’s congregation, which continues to send out missionaries to the four corners of the earth. Currently, approximately 40% of the church’s annual budget is dedicated to its mission’s program.

Since Park Street Church’s founding in 1809, it has sent out over 450 missionaries to fulfill the Great Commission which Jesus gave to his disciples: “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore, go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:18-20). The congregation at Park Street Church continues to believe that the Gospel of Jesus Christ brings light to the world.

Park Street Church, a Congregational church built in 1809 at the corner of Park Street and Tremont Street in Boston, sent missionaries to Hawaii starting in 1819. Photo from 2014 courtesy of Wikipedia.

Kawaiaha’o Church, a Congregational church in Honolulu completed in 1842, is sometimes called the Westminster Abbey of Hawaii. The church was founded by missionaries from Boston inspired by a native Hawaiian convert to Christianity. Photo by Mark Miller, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Robert H. Bradley is Chairman of Bradley, Foster & Sargent Inc., a $3.97 billion wealth management firm that has offices in Hartford, Connecticut and Wellesley, Massachusetts. Read other articles by him here.