Elizabeth Holmes and the Theranos Hoax: A 21st Century Ponzi Scheme

By Robert Bradley | January 27, 2020, 22:44 EST

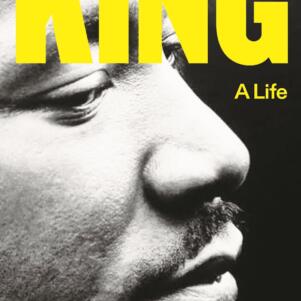

Elizabeth Holmes in 2014. Photo by Max Morse for Tech Crunch, via Wikipedia.

If something seems too good to be true, it probably is.

(American Proverb)

Some years ago, we wrote a commentary about Charles Ponzi, who has gone down in the history of finance as the father of the Ponzi Scheme. In 1920, Ponzi, an Italian immigrant whose base of operation was 27 School Street in Boston, enticed first dozens, then hundreds, and finally thousands to invest in his get-rich-quick scheme. He promised to pay back in 90 days the principal invested plus 50%. In January, 18 people invested a total of $1,770 with Ponzi’s Securities Exchange Company. In February, 17 more invested $5,290. By June, $2.5 million was invested by small-time investors throughout New England. In July, the final month of the scam, $6.5 million flowed into Ponzi’s coffers. By the time the fraud was uncovered the following month, almost $10 million had been “invested” with Charles Ponzi (the equivalent of more than $100 million in current dollars).

Ponzi had promised investors that by purchasing and selling International Reply Coupons (postal coupons), he would be able to generate these outsized returns. Instead, he used some of the money “invested” to pay off the people who wanted their money back. Although gaining global and long-lasting fame through the invention of a “Ponzi Scheme,” he would spend over twelve years in jail and then be deported back to Italy.

The Theranos Hoax

One hundred years later, we still encounter financial scandals, but the Theranos hoax was very different. Firstly, it was not primarily a manipulation of financial numbers. Theranos was a privately held health technology company, which claimed to have invented blood tests that needed only very small amounts of blood. The company trumpeted their blood testing system as a huge technological breakthrough. Secondly, Theranos existed because of the energy, drive, intelligence, beauty, and charisma of one person — its founder, chairman and CEO Elizabeth Holmes. Her image was that of a female, Silicon Valley, entrepreneurial rock star. And her vision for Theranos was that its blood-testing system would be a great boon for the health industry and millions of patients alike. The story of Theranos is the story of Elizabeth Holmes.

Youth (1984-2004)

In recounting the remarkable story of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos, we depend primarily on an outstanding book, Bad Blood, by a Wall Street Journal reporter, John Carreyrou, whose dogged investigative journalism exposed the Theranos scam. Elizabeth Holmes was born in Washington D.C.. Her mother, Noel Holmes, worked as a congressional staffer. Her father, Christian Holmes IV, worked for Enron and later the State Department and U.S. government agencies such as USAID and the Environmental Protection Agency. Both of her parents had distinguished family backgrounds, and her parents encouraged Elizabeth to live a purposeful life — not like some of her ancestors who had squandered the family fortune. When her father took a job at Tenneco, the family moved to Houston, where Elizabeth attended St. John’s — the leading local private school, where she became a straight-A student.

She was interested in science and computers and had already set her sights on becoming an entrepreneur. So naturally, she was attracted to Stanford with its proximity to Silicon Valley. Elizabeth was already familiar with Stanford, as she had learned some Mandarin Chinese and attended, while still in high school, Stanford’s summer Mandarin program. In the spring of 2002, Elizabeth was accepted at Stanford as a Presidential Scholar — a significant achievement. She chose to study chemical engineering as a pathway to biotechnology. The chairman of the chemical engineering department was Channing Robertson — a handsome and charismatic professor whom Elizabeth persuaded to allow her to help out in his research lab.

The summer after her freshman year, she went to Singapore as a summer intern for the Genome Institute of Singapore. Returning home in the early fall, she sat down at her computer for a week straight, and drawing from the technology she had learned in Robertson’s classes and from her internship, she wrote a patent application for an arm patch that would simultaneously diagnose and treat medical conditions. In early 2004, Elizabeth filed paperwork to start a company and dropped out of Stanford, having not completed her sophomore year.

Founding Theranos (2004-2009)

Using her tuition money as seed funding for the company, Holmes incorporated the company in Palo Alto as Real-Time Cures. The company’s value proposition was to perform blood tests, garnering large amounts of data, using only a few drops of blood derived from a pin prick at the tip of a finger. She always told people that her motivation was her fear of needles. In April 2004, she changed the name of the company to Theranos, creating a word derived from therapy and diagnosis. Her first employee was the Ph.D. student for whom she had acted as a research assistant at Stanford, Shaunak Roy; Professor Robertson joined the board as an advisor. Using her family connections, she raised a total of $6 million in 2004. To accomplish this, she presented a business plan that envisioned a patch that would painlessly draw blood through the skin using microneedles, transmitting the blood to a microchip which would analyze the blood and make a “process control decision” about how much of a drug to deliver. It would also communicate the findings to the patient’s doctor.

It soon became clear that producing this patch would not be easy to accomplish, and the company pivoted to a cartridge-and-reader system whereby the patient would prick a finger and draw a small sample of blood, placing it in a cartridge that looked like a credit card. The cartridge would slot into a machine called a reader, and pumps would push the blood into channels where the blood would be read and a result tabulated. After 18 months of work, by the end of 2005, they had a prototype that they thought would work. Over the next several years, the engineering staff worked to produce a machine which would be able to produce the necessary data from such small amounts of blood. They came up with a machine that would allegedly analyze the blood and calculate accurate results. They called the machine the Edison. Theranos then visited a number of major drug companies to sell them on using the Edison.

Malfunctioning Edison

The only problem was that the Edison often didn’t work as advertised. In fact, in a key demonstration in Switzerland at Novartis, the machine failed badly, and fake numbers were transmitted to Novartis. However, Theranos indicated that several major pharmaceutical companies had committed to use its blood-testing system to monitor patients’ responses to new drugs. Largely due to these commitments, Holmes raised another $32 million in a second funding round, making a total of $47 million she had raised since 2004. Noted venture capitalist Don Lucas and Oracle CEO Larry Ellison both invested in Theranos. In fact, Elizabeth frequently had Sunday breakfast at Ellison’s home, where he acted as her mentor. And the second round of funding valued Theranos at $165 million. When chief financial officer Henry Mosley met with Holmes to discuss the problem that Edison only worked erratically and that the data transmitted to Novartis was fake, she fired him on the spot. There had always been rapid turnover of staff, but this was extraordinary. In 2007, Edmond Ku, the head of engineering, was let go. Later that year, Elizabeth’s co‑founder, Shaunak Roy, left the company as well.

By mid-2008, Elizabeth had fired thirty employees, not including the twenty in the engineering department who had gotten the ax when Emond Ku was let go. But another crisis arose that year. Several key Theranos staff members went to a board member and told him the revenue projections that Elizabeth was presenting at the board meetings were greatly exaggerated — especially as the product was not finished and was unreliable. When the board convened, they met without Elizabeth and made the decision to remove her as CEO, as she was too young and inexperienced for the job. However, when they called her in to inform her of their decision, she persuaded them in a two-hour meeting, with just the right amount of charm and contrition, to reverse their decision.

Walgreens and Safeway

In 2010, Elizabeth traveled to Walgreens’s headquarters in Deerfield, Illinois to give a presentation on Theranos’s blood-testing product. A procedure that would make blood tests less painful and more widely available, so that it could be an early warning system against disease, appealed greatly to the Walgreens team. Furthermore, Walgreens believed that a partnership with Theranos would help them compete against their great rival, CVS. Walgreens agreed to a pilot project that would place Theranos blood readers in thirty to ninety Walgreens stores by the middle of 2011. Customers would be able to get their blood tested with just a prick of a finger and get the results within an hour. Walgreens committed to purchase $50 million of Theranos cartridges and lend the company $25 million. If all went well, the partnership would be expanded nationwide. Around the same time, Theranos inked a similar deal with Safeway. Under the agreement, Safeway was to loan $30 million to Theranos, and committed to undertake renovations in many of its stores to make room for clinics where its clients would have their blood tested on Edisons.

The danger, of course, was that if the Theranos machines were to malfunction or provide inaccurate readings of a customer’s blood, it could have grave consequences. On the one hand, a reading could pinpoint a nonexistent problem, which could worry a patient and necessitate a visit with a physician even if the patient would actually be healthy. On the other hand, if the client had a real health problem and the blood test did not pick it up, the result could be life-threatening. This is the main reason why machines like the Edison are regulated either by the Food and Drug Administration or the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (through its arm called Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments).

Theranos Corporate Culture

Legendary professor of business and consultant Peter Drucker once wrote, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” This was never truer than at Theranos. Elizabeth Holmes was passionate about her vision of creating a company that would be of enormous benefit to both patients and the medical profession. She was a superb saleswoman. With her enthusiasm, intelligence, work ethic, drive, good looks, and charisma, she could persuade anyone of almost anything. But she also had some grave shortcomings. One is that she demanded unmitigated loyalty from her staff. If anyone crossed her or strongly disagreed with her, she saw it as disloyalty, and in most cases the offender would be fired in short order.

Another character flaw was Holmes’s need for extreme secrecy; as time went on, it seemed to reach the point of paranoia. Upon joining the firm, employees were required to sign non-disclosure agreements), which was not unusual in technology companies. But all outgoing email messages by employees were routinely monitored by the company – allegedly to make sure that no secrets were purloined. When employees resigned or were terminated, the company went to extraordinary lengths to ensure that only personal items left the company. There were numerous occasions when employees were threatened with legal action if they revealed anything at all about the company, technological or not. In one case, the laboratory director had come to believe that Theranos was breaking the law. He had also been required to assure physicians of the accuracy of flawed blood readings. When he resigned, the company insisted that he sign, under penalty of perjury, a statement which read: “I do not have any electronic or hard copy information relating to Theranos in any location including personal laptops or desktops, trash/deleted folders, USB drives, home, car, or any other location.” He had been sending copies of emails to his personal email accounts in order to have a record of some of the unethical and even illegal actions of the company. When he refused to agree to delete the emails (having monitored all outgoing traffic, the company knew of his personal emails), they brought in their heavy legal guns and threatened to sue him. Ultimately, he deleted the emails and signed, following the advice of his lawyer, who counseled that his legal fees could bankrupt him.

At Theranos, there was also a culture of intimidation. In Beijing, at Stanford’s Mandarin program that Elizabeth Holmes had attended while still in high school, she met Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, who took her under his wing. Twenty years older than Elizabeth, Sunny was born and raised in Pakistan and came to the United States for his undergraduate studies. While working in the tech world he had struck it rich during the Internet bubble while briefly serving as president and chief technology officer for CommerceBid, a B2B e‑commerce company. Commerce One acquired the startup for $232 million in cash shortly after he joined the company, and Sunny walked away with $40 million. Shortly thereafter, the Internet bubble burst and Commerce One eventually filed for bankruptcy. Several years after, when Elizabeth was founding Theranos, Sunny became her close friend and mentor. In 2005, they began living together. In 2009, he joined Theranos, eventually becoming president and chief operating officer. Unfortunately, it appeared that the board of directors was not aware of Elizabeth’s relationship with her chief operating officer, who was much older than she was.

Employees characterized Sunny as a dishonest bully who managed through intimidation. And with his office next to Elizabeth’s, he became her alter ego, involved in every aspect of the company. The culture of fear and the insistence on extreme loyalty led to the extremely high rate of employee turnover. It also deterred associates from reporting unwelcome news or results. Based on its culture of fear and covering up problems, Theranos was a toxic mix destined for trouble.

Elizabeth Holmes’s Amazing Ability To Persuade

The existence of Theranos was predicated on Elizabeth Holmes’s powers of persuasion. To think that a young dropout from Stanford could master the medical technology necessary to create a cutting-edge blood-analyzing system based on several drops of blood was beyond improbable. But she managed to convince a long line of highly intelligent and successful people to throw their lot in with her. First was Channing Robertson, the Stanford engineering professor whose reputation lent her credibility. Next were iconic venture capitalist Donald Lucas and Oracle CEO Larry Ellison. She also managed to persuade major companies such as Walgreens and Safeway of her blood-testing machines. Finally, she recruited the following remarkable group of wise men from previous decades to join Theranos’s board of directors:

Bill Frist U.S. Senate Majority Leader

Henry Kissinger U.S. Secretary of State

Richard Kovacevich Chief Executive Officer of Wells Fargo

James Mattis Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff

Sam Nunn U.S. Senator, Georgia

William Perry U.S. Secretary of Defense

Gary Roughead Admiral, U.S. Navy

George Shultz U.S. Secretary of State

Holmes was passionate about her vision of a blood-testing system that would help humanity, and she was able to communicate it incredibly well. She had a strong will and great charisma. Together with her good looks, her charm ,and her undoubted intelligence, there were few that she could not persuade. She seemed most effective at winning the support of older and experienced men, as the list above demonstrates.

Tyler Shultz — George Shultz’s Grandson

After graduating from Stanford, Tyler Shultz was deeply inspired by Holmes’s vision and joined Theranos. Tyler soon discovered that the Edison often gave incorrect or misleading results. He brought it and other concerns to Elizabeth, who dismissed them out of hand. As his concerns mounted, he reached out to the New York state health department in an anonymous email, requesting an expert opinion. The department responded that Theranos’s proficiency-testing of its machines was a form of cheating and in violation of state and federal law. Armed with this information, Tyler went to his grandfather, George Shultz, with his concerns. Tyler also told him that he could no longer be a party to what was going on and that he planned to quit. The 92-year-old former Secretary of State prevailed upon Tyler to take it up with Elizabeth again. When he did, a response came not from her but from Sunny in a scathing rebuke. When his grandfather sided with Elizabeth, Tyler quit. At this time, Theranos’s last round of private funding pegged its market value at $9 billion. Elizabeth’s net worth was now $5 billion on paper.

Legal Bullying

About the same time, John Carreyrou, the future author of Bad Blood, got a tip about the wrongdoing at Theranos. As he began to do investigative research for the Wall Street Journal, he become more and more intrigued – especially in view of the huge amount of publicity Elizabeth Holmes was receiving in adulatory articles in his own paper, The New Yorker, Forbes, and other magazines. A young, female Silicon Valley entrepreneur worth $5 billion! Eventually Carreyrou touched base with Tyler Shultz as well as others who had quit. To keep the story from becoming public, Theranos hired David Boies’s firm to do everything possible to keep the truth concealed. (Boies was the famous litigator who had prosecuted Microsoft on behalf of the U.S. government among other high-profile cases). The firm’s basic tactic was to threaten to sue anyone alleging illegal acts of wrongdoing by Theranos for breaching their nondisclosure agreements. Ultimately, it cost Tyler Shultz and his family $400,000 in legal costs to defend his talking to a Wall Street Journal reporter and exposing Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos’s wrongdoing. It also severed Tyler’s relationship with his grandfather, George Shultz. Other employees, who did not have the resources to defend themselves, were fearful of talking with Carreyrou.

The Downfall

As the Wall Street Journal prepared to publish the story about Theranos’s misdeeds, Boies and his colleagues went after the paper, threatening to for publishing trade secrets and defaming Theranos. They assaulted John Carreyrou’s journalistic integrity. Holmes even tried to persuade Rupert Murdoch, who had recently made a $115 million investment in Theranos, and whose company owned the Wall Street Journal, to kill the story. He refused. The story, with many incriminating details, was published in October 2015. It was a bombshell. Holmes immediately denied the story and appeared on Jim Cramer’s Mad Money to rebut it. In 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services banned Holmes from owning or operating a blood-testing service for two years, and Walgreens ended its relationship with Theranos. In 2017, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission initiated civil and criminal action against Theranos and its officers. At its height, the company had 800 employees. By 2018, all the employees had been laid off, and the company began the final stages of dissolution. Also in 2018, a grand jury indicted Holmes and Balwani on nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. Each pleaded not guilty. The trial is scheduled to be held in July 2020. If convicted, they face up to 20 years in prison.

A Cautionary Tale

What can investors learn from this cautionary tale? Unlike the Ponzi scheme, this was not a case of seeking to make extraordinary gains in a short period of time. This was a case where experienced, knowledgeable venture capitalists, entrepreneurs statesmen and investors were taken in by a well-intentioned but ambitious, persuasive entrepreneur — with a vision for a company that would benefit humanity. Character and integrity are vitally important, and often it is difficult to determine whether a CEO has it or not. Charm can be a dangerously seductive thing. Facts are what really matter. Ronald Reagan’s famous saying still rings true: “Trust but verify.” And finally, if something appears too good to be true, it probably is too good to be true.

Robert H. Bradley is Chairman of Bradley, Foster & Sargent Inc., a $4.2 billion wealth management firm that has offices in Hartford, Connecticut and Wellesley, Massachusetts. Read other articles by him here.