‘Crusader’ Is Not the Problem; ‘Holy Cross’ Is the Problem

By Matt McDonald | March 24, 2017, 16:51 EDT

The students who run the newspaper at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts want to ditch “Crusader” as the paper’s name. The president of the college wants to get rid of it, too, as the school’s mascot and nickname for sports teams.

Some students on campus, one of the editors explained, “do not feel safe here” because of the name. The college president wants to “engage in dialogue” about it.

But if dialogue is to be fruitful, it’s got be honest. The real problem isn’t “Crusader,” a word that sends most people scurrying to Wikipedia when asked about the details.

The real problem is Holy Cross.

What cross are we talking about? The one Jesus of Nazareth was killed on. What makes it holy? The Christian assertion that Jesus’ death on it made it possible for human beings to be saved.

Why do Christians think that?

Hold on to your helmet.

They think Jesus is God.

This is the same Jesus, by the way, whose closest followers quoted him as saying some of the least ecumenical things on record.

“I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6)

“Without me you can do nothing” (John 15:5)

“No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6)

“Unless you eat my body and drink my blood you have no life in you” (John 6:53)

“Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned” (Mark 16:16)

“He who rejects me rejects him who sent me.” (Luke 10:16)

“… before Abraham was, I AM” (John 8:58)

I mean, can’t we all just get along?

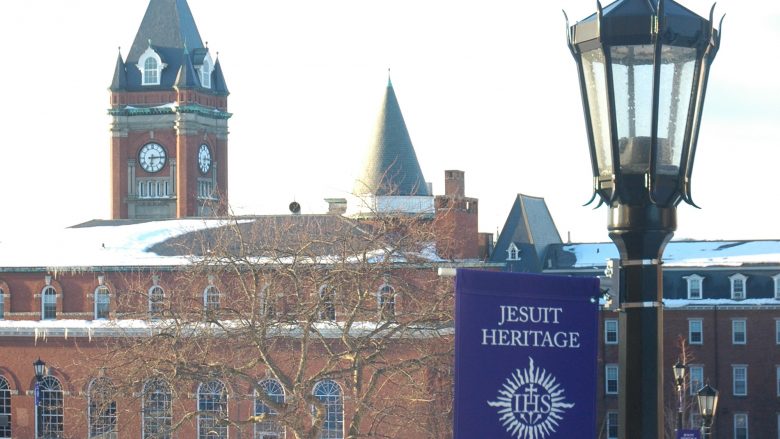

Father Philip Boroughs, a Jesuit and the president of Holy Cross, got the ball rolling on this one by setting up a committee in the fall of 2015 to discuss whether a couple of buildings on campus should be renamed in light of some problematic facts concerning the historical figures commemorated.

He also asked the committee “to be aware of other issues of naming and memorialization on our campus which might need to be reviewed.” Apparently, that refers to “Crusader,” but if that’s the case, it doesn’t go nearly far enough — because the two terms (“Holy Cross” and “Crusader”) are so closely connected that an academic might even call them “inextricably intertwined.”

The Crusades have a long, complicated history that began in 1095 when a Byzantine Christian emperor was having problems with Muslim armies on his eastern front and the pope called for Roman Catholics in Europe to help him out and free the Holy Land from the Muslims, too.

From there it gets more complex. Wars sanctioned by the pope occurred several times over the next couple of hundred years, all known these days by the more modern term Crusade.

The Crusaders were a mixed bag. Some had high ideals and lived up to them — their numbers included men who gave up their lives to become warrior-monks so they could protect pilgrims who came to the sites where Jesus lived, died, and (according to Christians) rose from the dead. Some, though, joined mainly for adventure and plunder — and their deeds included sacking Constantinople, the capital city of their Christian allies, for fun and profit in 1204.

In short, they included the good, the bad, and the ugly — something like humanity.

Here’s the point, though: A crusader was one who was said “to take the cross.” Crusaders put a cross on their chest. They ventured east to free (from a Christian point of view) the land where Jesus suffered and died on a cross. They believed that Jesus had made atonement for their sins by his death on a cross. At their best, they dedicated their lives to Jesus by embracing his cross.

In other words, “Crusader” isn’t just one possible nickname for a school that calls itself “Holy Cross”; it’s the obvious one.

So maybe it’s time to rethink the name of the school.

What Students Think (Or At Least Some of Them)

The editors of The Holy Cross Crusader called a meeting to discuss the name on campus last week that drew about 80 people, most of them students. Participants should be congratulated on the atmosphere at Rehm Library, which included no interrupting, no shouting, and no personal attacks. It’s the sort of calm public discussion of a contentious matter that is becoming hard to envision on a college campus in America.

Another happy occurrence: The pro-change people abandoned one of the reasons given by faculty members who sent a letter to the newspaper in February. The letter noted (in part) that a faction of the Ku Klux Klan publishes a newspaper also called Crusader. The nonsensical argument that the college’s student newspaper should give up its name because a tiny marginal group with a bad world view also picked the same name evaporated during the discussion Thursday, March 16.

Still, that leaves a harder problem. It is clear that there is a divide on the campus between people who like and value the Catholic identity of the college and people who don’t — or at least who don’t value it so much that they are unwilling to water it down to try to make other people feel comfortable.

One speaker, apparently an editor of the newspaper, tried a neat debater’s trick by switching the burden of proof from the affirmative to the negative. (Speakers didn’t mention their names, no none are mentioned here.)

“I would just suggest that, going out on a limb to say that some people are offended or do not feel welcome because of this name,” he said. “And I would pose to you, if you are for ‘The Crusader,’ is there something inherently offensive or unwelcoming or something that makes you feel unsafe about changing the name? Because as it currently stands there are students in this room, and students across campus, who do not feel safe here, or who do not feel like their culture is welcome here because of the current name of the newspaper.”

Where to begin?

The word “safe” jumps out. Why is it a priority? Are there armed marauders on the campus seeking out non-Catholics and trying to drive them off College Hill, spurred on by the name of the newspaper? If not, are there students going around insulting other people’s culture — and, again, inspired by the newspaper? Or is it just the word “Crusader” that’s doing all that?

If it’s merely emotional equanimity we’re talking about, then “safe” is at risk for losing its meaning.

Note that it’s the defenders of the status quo who are called out to make a case to keep what already exists, simply because some students on campus say they are offended.

Who are these people? Well, Muslims.

“I know plenty of Muslim students on campus that are weirded out by the fact that we do represent ourselves by a crusader,” one junior said.

Oddly, no speaker identified himself as a Muslim or made an argument suggesting personal offense at the name “Crusader.” It wasn’t clear that there were any Muslims in the room. But let’s assume that at least some Muslims on campus don’t like the name.

Clearly, a Muslim would not hold to a Catholic view of things, or even a Christian view of things. Clearly, a Muslim would be unlikely to feel the same way about the Crusades that a Christian might.

That brings us to the heart of the matter: What is the point of the school?

One female undergraduate thought “Crusader” is an “outrageous” name for a student newspaper because it suggests a lack of journalistic objectivity, when the paper should be “representative of a bunch of different opinions.” The aura of possible offensiveness also bothers her.

“I think if this is offensive to anyone in the student body, why would we want our paper to be called it?” the girl said.

She suggested “The Purple,” which is Holy Cross’s color, as a name everyone could rally around. But then another student pointed out that purple was the color of the Roman emperors, who were known for their conquering tendencies.

It might also be pointed out that purple is associated with Jesus, whom Christians regard as a king, and whose throne was the Cross.

Third base. (As Abbott and Costello might say.)

Defenders of “Crusader” say it’s ingrained in the college’s history and culture, and that it expresses an aspect of Catholicism. And they think that’s a good thing.

“Above all, you chose to come here, and it is a Catholic school,” one female student said.

But not so fast, another student said. A lot of kids go to Holy Cross not because it is Catholic but because it offers generous financial aid, has a good reputation, and provides a good education. Shouldn’t those students be represented?

He didn’t add, but might have: And are they really represented by a cross? Holy or otherwise?

The administrators’ decision to change the logo in 2014 supports this sort of argument. Gone is the cross-wearing, sword-wielding crusader. He has been replaced by a more ambiguous shining sun. The official explanation in the college’s quarterly magazine is that the shining sun is an image of the Jesuits — but you’d almost have to be a Jesuit to know that. And since the explanation omits any reference to the old knight, the suspicion is that the powers-that-be prefer not only that he be dead but that he also be buried.

The lack of forthrightness calls to mind another aspect of the history and culture of the famous religious order that runs the institution.

Say, there’s an idea. Why not call it Jesuitical College?

Matt McDonald is Publisher and Editor-In-Chief of New Boston Post.